The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

What The FDA’s Crackdown On Synthetic Food Dyes Could Mean For Cancer Prevention

FDA Approves Natural Dye As Part of Broader Effort To Eliminate Synthetic Additives

On July 14th, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the approval of Gradenia Blue Interest Group’s (GBIG) color additive petition to use the color gardenia (genipin) blue in various foods, following the manufacturing practice standards. It is one of the four colors derived from natural sources approved by the FDA for use in foods in the last two months. Genipin, the approved dye, has been reported to have anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, neuroprotective, and antithrombotic effects.

This announcement is not surprising, as Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, made it a priority to phase out the use of synthetic, petroleum-based dyes from the nation’s food supply. In April 2025, the FDA announced that it would work with the industry to eliminate the six remaining synthetic dyes from the food supply, including FD&C Green No. 3, FD&C Red No. 40, FD&C Yellow No. 5, FD&C Yellow No. 6, FD&C Blue No. 1, and FD&C Blue No. 2.

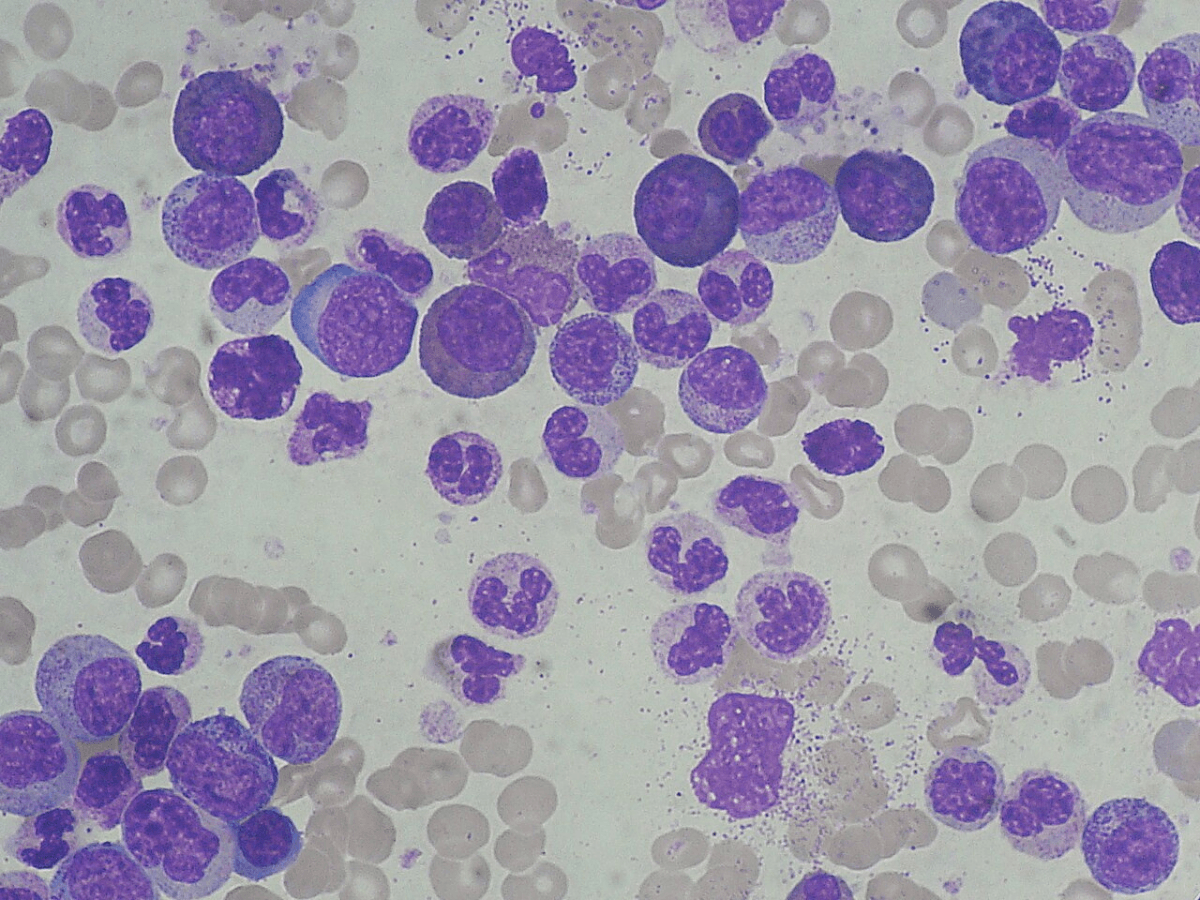

Research Shows That Synthetic Food Dyes Are Linked to Cancer

For many decades, research data suggests that these synthetic food dyes may be linked to cancer development.

If you take a look at any rainbow-colored candy, soda, cosmetic, or even over-the-counter cough syrup, nestled among the small-print ingredients is an artificial food dye: Red 3, Red 40, Yellow 5, Blue 1, Blue 6. These food dyes are originally produced from coal tar or petroleum. And while their vibrant colors may be visually appealing, research shows that their detrimental effects may impact major organs in the body, particularly in causing cancer.

In a 2023 study published in Toxicology Reports, researchers found that Red 40 damages DNA, causes inflammation in the mouse colon, and disrupts the regulation of the important tumor suppressor protein p53. The findings from this study are consistent with previous reports showing that increased use of Red 40 (also known as Allura Red AC) in ultra-processed foods coincides with the rise in early-onset colorectal cancer.

Similarly, in the 80s, researchers in Japan found that Red 3 and Red 105 promoted the development of thyroid tumors in rats, raising concerns about their potential harm to humans. While it was noted that the specific way Red 3 causes cancer in male rats does not apply to humans, the findings still contributed to ongoing scrutiny. In January 2025, the FDA revoked authorization for the use of Red 3 in food and ingested drugs. Manufacturers have until 2027 and 2028 to reformulate products that contain this dye.

Findings from correlational studies in humans support the conclusions from animal research regarding synthetic food dyes. A large cohort study involving 102,485 French adults tracked exposure to food dyes through repeated 24-hour dietary records over 13 years. The study identified 3,511 cancer cases during follow-up, with participants who had higher exposure to food dyes showing increased overall cancer risk, including higher risks for breast and colorectal cancers.

Notably, while industry-sponsored studies of Blue 1 reported no evidence of cancer-causing properties or other toxicity in rats and mice, other researchers reported its genotoxic and cytotoxic potential, suggesting that caution should be taken when using it as an additive. Similarly, another study revealed a significant increase in brain gliomas and malignant mammary gland tumors in rats that ingested Blue 2, marking it unsafe for human consumption.

What Companies Are Saying About The New Rules To Eliminate Synthetic Food Dyes

Since the FDA announced the gradual elimination of these synthetic dyes in food in the spring, about 40% of the food industry has committed to a voluntary phase-out of such dyes. Although few companies are hesitant or not committed, citing that natural dye alternatives are less stable, less vibrant, and may affect the taste of their products. States like Texas and West Virginia plan to enforce laws that require bans or warning labels on food containing synthetic dyes between 2027-2028.

Are There Better Alternatives To Synthetic Food Dyes?

While natural dyes are far from perfect, they do offer health benefits. For example, carotenoids, anthocyanins, beetroot extracts, and turmeric all have antioxidant properties, which have been reported to have anti-cancer effects. Natural dyes do have their challenges: they are expensive, fade over time, and have intrinsic flavors that may clash with a food's taste.

However, just because a dye is natural, it does not mean it is automatically healthy, as all food dyes are from nature, including petroleum and or coal-based ones. For instance, carmine (red 4 or E120), a bright red food dye, is obtained from the dried bodies of an insect, and it is commonly used in cosmetic, food, and pharmaceutical industries. It has been reported to cause severe allergies and potentially mutate DNA, potentially accelerating cancer development.

What Could A Synthetic Food Dye Ban Mean For Cancer Prevention In The U.S.?

Several countries have banned or restricted the use of food dyes due to concerns about their potential health risks, including cancer. Red 40, yellow 6, and yellow 5 are under strict regulations in Europe. Countries like Norway, Germany, and Switzerland have restricted or banned the use of Red 40.

Since cancer is a multifactorial disease shaped by both genetics and lifestyle, dietary choices can impact its development. Yes, individuals can make healthier choices by reading ingredient lists, selecting whole foods, or using natural coloring agents like beetroot and turmeric. However, sometimes a dye's name can be ambiguous or implied, socioeconomic factors might limit the ability to choose whole foods, and sourcing natural coloring can be expensive and time-consuming. Therefore, a comprehensive ban on synthetic food dyes would support individual efforts to select healthier options.

Synthetic food dye is just one of many dietary components containing potential carcinogens. But for those who primarily consume foods high in synthetic food coloring, phasing out these dyes would significantly reduce their exposure to potential carcinogens.

Pressure has been mounting on the FDA for years, as many countries have already banned food dyes still allowed in the U.S. Now, with approvals for alternative dyes and the phase-out of harmful synthetic ones underway, it will be important to watch for studies examining how these changes affect cancer incidence trends in the years to come.

Works Discussed

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, April 22). HHS, FDA to phase out petroleum-based synthetic dyes in nation's food supply. FDA. Retrieved July 16, 2025, from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/hhs-fda-phase-out-petroleum-based-synthetic-dyes-nations-food-supply

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, July 14). FDA approves Gardenia (genipin) blue color additive while encouraging faster phase-out of FD&C Red No. 3. FDA. Retrieved July 16, 2025, from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-gardenia-genipin-blue-color-additive-while-encouraging-faster-phase-out-fdc-red-no-3

-

O'Donnel, J. (2022). The food dye is cast: What they are, why we need them, and if they are killing us. The Synapse: Intercollegiate Science Magazine, 31(1), Article 4. https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/synapse/vol31/iss1/4

-

Sultana, S., Rahman, M. M., Aovi, F. I., Jahan, F. I., Hossain, M. S., Brishti, S. A., Yamin, M., Ahmed, M., Rauf, A., & Sharma, R. (2023). Food Color Additives in Hazardous Consequences of Human Health: An Overview. Current topics in medicinal chemistry, 23(14), 1380–1393. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568026623666230117122433

-

Olas, B., Białecki, J., Urbańska, K., & Bryś, M. (2021). The Effects of Natural and Synthetic Blue Dyes on Human Health: A Review of Current Knowledge and Therapeutic Perspectives. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 12(6), 2301–2311. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmab081