The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

Implementation Science In Cancer: Where Are We Today?

Perspective

Introduction

Is medical innovation enough to drastically lower the grim cancer statistics published each year? A staggering 7 million results appear when you type “cancer” into Google Scholar, a search engine for scholarly literature. These papers cover every aspect of cancer research, from basic science and preclinical studies to epidemiology and clinical trials, spanning the entire cancer research pipeline. With so many discoveries emerging, it begs the question: where do we stand with implementing these findings into clinical practice?

What is Implementation Science?

Implementation science is a term used to describe the adoption and use of evidence-based interventions in targeted settings, including schools and healthcare facilities, to improve population health. In other words, improving access to new treatment modalities makes it easier for people to benefit from these advancements. The roots of implementation science can be traced back to the inception of evidence-based medicine, a field pioneered by the British epidemiologist, Archie Cochrane, in the 1970s. He recognized the importance of synthesizing high-quality evidence to guide clinical decisions. So, he called for the collection of systematic reviews in healthcare, leading to the creation of the Cochrane Collaboration.

The National Cancer Institute’s Efforts to Bridge the Research-to-Care Gap

Over the past few decades, the United States has seen rapid growth in implementation science. In 2019, as part of the Cancer Moonshot initiative, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) launched the Implementation Science Centers in Cancer Control (ISC3). The goal of ISC3 is to promote the development of research centers within community and clinical settings. This would allow better adoption, implementation, and sustainment of evidence-based cancer control interventions. Within this center, there are two featured initiatives: Consortium for Cancer Implementation Science (CCIS) and Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs (EBCCP). CCIS aims to build capacity, increase collaboration, and support implementation science activities in cancer. On the other hand, EBCCP has a searchable database of evidence-based cancer control programs, where the public or healthcare professionals can easily access information on screenings, vaccinations, survivorship, and informed decision making, among others. Together, these two initiatives help enhance collaboration amongst different areas of cancer care.

Why Evidence-Based Cancer Interventions Are Slow to Reach Patients?

Undoubtedly, implementation science incorporates insights from research, practice, and policy to close the gap in pivotal aspects of cancer care. But are we any closer to bridging this gap?

Several studies published in 2006 highlight why we must renew our commitment to prioritizing implementation science in cancer care. Bauer and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial across 11 sites in the US Department of Veteran Affairs (USVA) to test the Collaborative Chronic Care Model (CCM) for bipolar disorder versus regular treatment. CCM is defined as “an organization of care that emphasizes the patient's development of illness management skills and supports provider capability and availability to engage patients in timely, joint decision making about their illness." At the three-year follow-up, CCM showed a significant positive impact on mental health and overall quality of life. A parallel study that used a similar model was conducted in Washington State. Yet, within a year after the studies ended, CCM was not incorporated into clinical practice for patients with bipolar disorders. It was reported that clinicians who participated in the CCM studies returned to administering the standard form of care to patients. This example shows the hesitancy to adopt new evidence-based studies into clinical practice, and cancer care is no exception to this barrier.

The Disconnection Between Cancer Research and Clinical Practice

The long-standing practice in medicine is that it can take up to 20 years for a clinical innovation to be integrated into practice. The gap between research and clinical practice can be attributed to the speed of modern biomedical research outpacing the natural rate at which society absorbs information. Also, much of the biomedical and pharmaceutical cancer research enterprise is far removed from the cancer hospitals and community clinic settings. Hence, the reduced collaboration between researchers and physicians creates a disconnection that hinders the implementation of a novel intervention in the clinic.

For example, imagine a researcher developing a novel treatment approach. They progress from ideation to preclinical studies to clinical trials and regulatory approval, demonstrating remarkable efficacy. Afterward, the researcher returns to the laboratory to develop a new idea or refine a prior success, continuing the cycle.

Moreover, clinical studies often focus on efficacy but are not designed to address the adoption and sustainability of an approved medical intervention in practice.

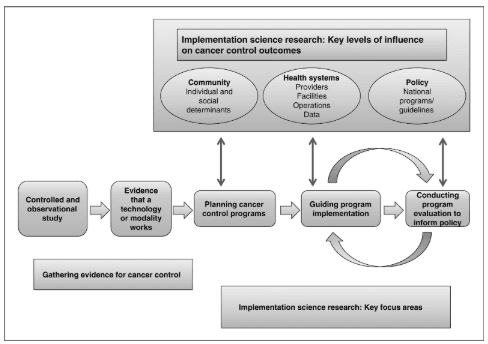

The role of implementation science in cancer research (Image by Sivaram et al., 2014).

The role of implementation science in cancer research (Image by Sivaram et al., 2014).

Strategies for Improving Cancer Care Delivery

Cancer care delivery research has been proposed to resolve this issue, however, research efforts in that area are not well-informed on the best implementation science and theories. Besides the regular workflow in the cancer research pipeline, an additional step evaluating the implementation of an intervention is necessary to improve patient outcomes and minimize the gap within cancer care. More than 100 implementation science theories and frameworks have been proposed to guide the selection of implementation strategies and pinpoint factors that would help with sustainability.

For example, one study proposes a Strategic Implementation Framework. It synthesizes existing models to guide the implementation process. This framework covers three stages: setting the stage, active implementation, and monitoring, supporting, and sustaining change. Each stage involves specific strategies, such as identifying champions, developing educational materials, and implementing performance metrics. Also, the framework suggests identifying barriers and facilitators, building coalitions, developing training materials, revising team roles, and adjusting workflows to accommodate frailty assessments. By systematically addressing these aspects, the framework aims to improve the integration of evidence-based practices into cancer care delivery and ultimately enhance patient outcomes.

Expert Insights: Dr. Mazyar Shadman on Translating Research into Practice

Similarly, systemic changes at the institutional level are instrumental for advancing implementation science in cancer care. We met with Dr. Mazyar Shadman, an associate professor, medical director of cellular immunotherapy, and Innovators Network Endowed Chair at Fred Hutch Cancer Center. Dr. Shadman explains the collaborative process at Fred Hutch, where scientists, clinicians, and industry partners work together to translate laboratory discoveries into safe and effective treatments for patients, highlighting both successes and challenges in drug development and clinical research.

He stated, “You can see how the spectrum goes from the scientist who discovers a molecule or a pathway to investigators who conduct preclinical studies, then to those who bring new treatments to the patient level, carefully investigating safety and efficacy.” He further highlighted some of the challenges that impede or slow down the process of bringing a drug from bench to bedside. Dr. Shadman noted, “Drug development is challenging, expensive, and has a high risk of failure, but by collaborating across disciplines, we increase the chances of bringing new, effective treatments to patients. Even after FDA approval, we continue monitoring patients because there is always more to learn about toxicities, long-term effects, and how to refine treatments for better outcomes."

Addressing Cancer Disparities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

In addition to the efforts of academic institutions, organizations must collaborate to advance implementation science in cancer care. Researchers have found that around 65% of cancer deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Besides population growth and aging, this disproportionate cancer burden in LMICs stems from lifestyle-related risk factors such as tobacco use and poor diet, as well as high prevalence rates of infection-related cancers like cervical cancer. Furthermore, a lack of education and awareness in communities may worsen the number of cancer deaths in those regions. These individual challenges, combined with inadequate infrastructure and limited access to palliative and preventative care and resources, lead to cancer being perceived as a terminal disease in LMICs, further perpetuating the cycle of misinformation in those communities. Researchers indicate that focusing on community-based research and health systems research enhances the planning, execution, and evaluation of the impact of cancer control programs in LMICs.

Binaytara’s Mission to Build World-Class Cancer Hospitals in LMICs

Our organization prides itself on promoting the adoption of innovative and approved medical treatments into standard care. Medical innovation does not stop at the celebration of its promising efficacy. It is equally important to bring life-saving therapies into clinical practice to facilitate better patient outcomes. This endeavor is not without its challenges, especially in LMICs.

The co-founder of Binaytara, Dr. Binay Shah, stated, "Some of these implementation science projects, or major healthcare efforts in low and middle-income countries, are highly challenging, not just from a finance perspective, but from numerous other aspects. So it takes a lot of effort to establish a strong program, a good program, and a program that is going to be culturally appropriate and also impactful.”

We are currently working to build a comprehensive cancer hospital that will feature state-of-the-art care and infrastructure in the Madhesh Province of Nepal. This hospital is part of a larger global plan to build similar institutions in LMICs, with the ultimate goal of providing world-class cancer care and preventive health measures to underserved populations. In an organizational update, the chief development officer at Binaytara, Justin Marquart, highlighted, “ This 200-bed cancer hospital being built in Janakpur, Nepal, will provide comprehensive cancer care, including stem cell transplants, radiation therapy, and other essential services found in top cancer centers like Fred Hutch or MD Anderson. This hospital aims to serve over 6 million people in the province and also provide care for populations in northern India, where access to cancer care is severely limited.”

The Future of Implementation Science in Oncology

Binaytara is committed to driving systemic change that improves cancer patient outcomes in underserved communities. Ongoing efforts towards advancing implementation science at Binaytara include our expansive network of Continuing Medical Education (CME) and Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs, flagship conferences, and the OncoBlast app. These educational programs are designed with the principles of implementation science and health equity in mind. Similarly, according to our strategic plan, by 2029, we will establish an implementation science research center in Washington State. The center will focus on establishing projects in Implementation Science, Hematology and Oncology Education Research, and Global Oncology.

Implementation science offers a promising approach to tackling the challenges of integrating research findings into everyday cancer care. Despite their proven benefits, translating research into real-world healthcare settings remains slow and inconsistent. We are determined to make a broader impact by training healthcare professionals, establishing hospitals and programs, and facilitating policy changes that enhance implementation and access to care for communities.

Join us in our efforts to bridge the gap in cancer care and provide life-saving medication and infrastructure to communities in need.

Works discussed

-

Bauer, M. S., & Kirchner, J. (2020). Implementation science: What is it and why should I care?. Psychiatry research, 283, 112376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025

-

Lobb, R., & Colditz, G. A. (2013). Implementation science and its application to population health. Annual review of public health, 34, 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114444

-

Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC psychology, 3, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9

-

Sivaram, S., Sanchez, M. A., Rimer, B. K., Samet, J. M., & Glasgow, R. E. (2014). Implementation science in cancer prevention and control: a framework for research and programs in low- and middle-income countries. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 23(11), 2273–2284. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0472

-

Westfall, J. M., Mold, J., & Fagnan, L. (2007). Practice-based research--"Blue Highways" on the NIH roadmap. JAMA, 297(4), 403–406. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.4.403