The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

Prostate Cancer 101

During their lifetime, one in eight men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. At Binaytara, we are here to support patients every step of their cancer care journey. Our mission is to minimize cancer disparities by giving everyone access to evidence-based information that helps them make informed decisions. This introduction to prostate cancer is designed not just to inform you, but to empower you. When people are well-informed, they are better equipped to act, advocate, and engage fully in their own care.

Prostate Cancer Overview: What Is Prostate Cancer?

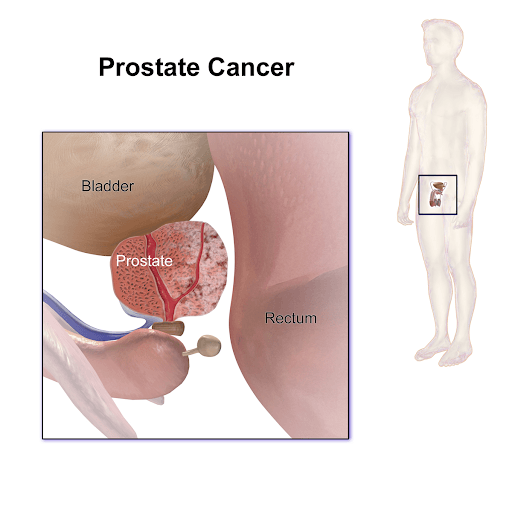

Prostate cancer refers to the abnormal growth of glandular cells in the prostate and is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in U.S. men. The prostate, located below the bladder, is part of the male reproductive system. Early-stage disease is often slow-growing, but aggressive variants can spread to bone and other organs, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. The Gleason score is a histologic grading system used to indicate prostate cancer aggressiveness and help predict how quickly it might grow and spread. A Gleason score of 6 or lower is considered low-grade and slow-growing, 7 is intermediate-grade, and 8–10 is high-grade and aggressive.

Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons

Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons

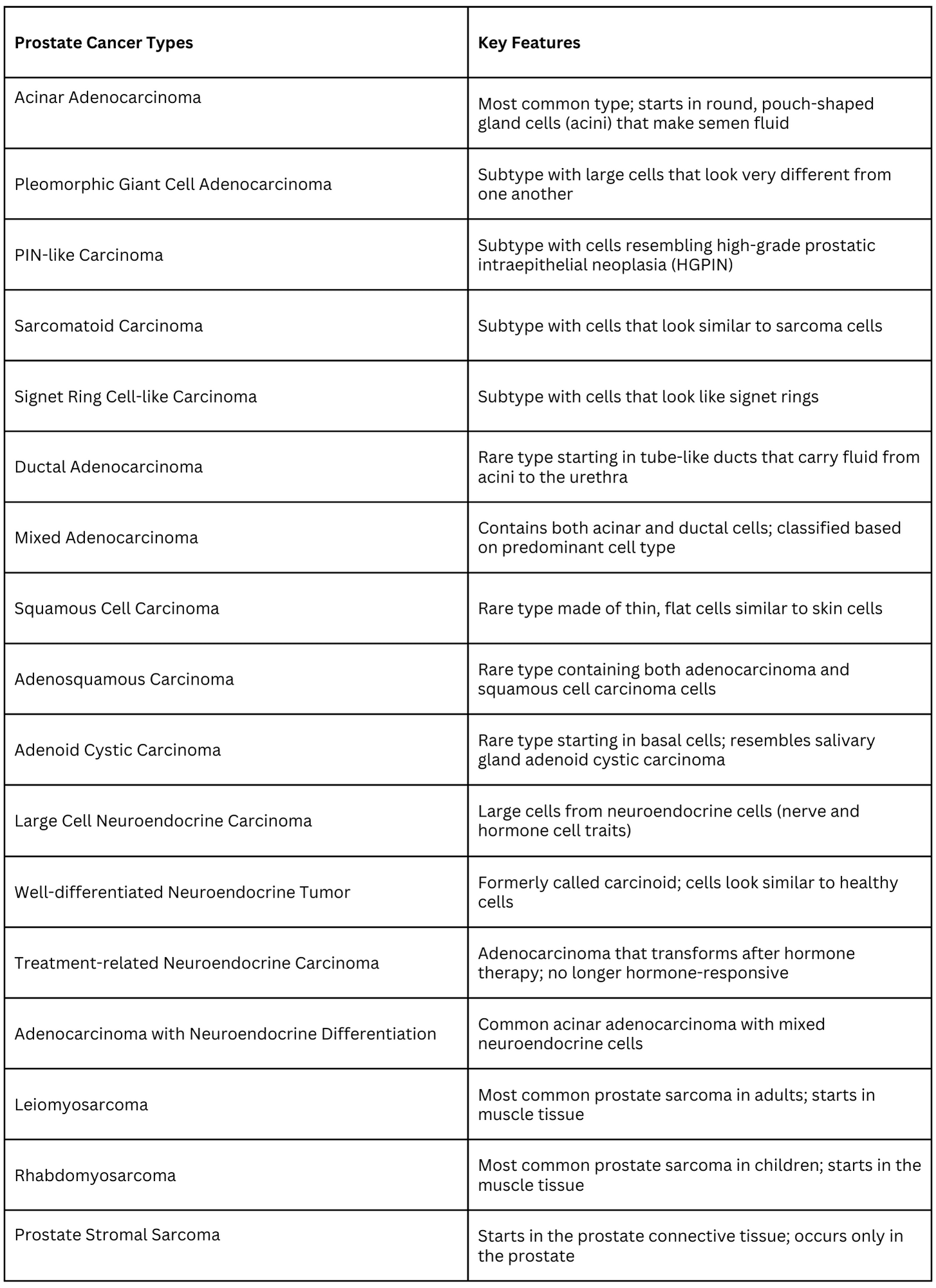

Types of Prostate Cancer

The vast majority of diagnosed prostate cancer cases are adenocarcinomas, referring to cancers that form in glandular tissues, ones that produce fluids or other substances. They can range from very low-risk, organ-confined tumors to high-risk or metastatic disease that can be castration-sensitive (mCSPC) or castration-resistant (mCRPC). The histologic and genomic features guide prognosis and therapy selection in clinical practice. These adenocarcinomas vary based on their histology and unique clinical features.

Prostate Cancer Trends: Incidence, Outcomes, and Health Disparities

Incidence declined from 2007 to 2014 with reduced PSA screening, then began rising about 3% annually, underscoring the need for risk-adapted screening and timely treatment. Prostate cancer represents roughly 15% of new male cancers in 2025, with diagnosis peaking at ages 65–74. Mortality trends reflect treatment and screening policies over decades, while incidence is tightly linked to screening intensity. Non-Hispanic Black men have the highest incidence and worse outcomes, driven by access, biology, and systemic inequities. Addressing disparities requires equitable screening, genetics-informed care, trial access, and supportive services. Socioeconomic factors and regional access influence outcomes across populations, necessitating system-level interventions.

Prostate Cancer Risk Factors

The lifetime risk of prostate cancer development is about 1 in 8 men. While the cause of prostate cancer is not exactly known, and anyone with a prostate can develop this disease, some factors increase the risk:

- Age: The risk of developing prostate cancer starts to rise significantly after age 55 and peaks at age 70-74.

- Family History: Having a father or brother with prostate cancer doubles your risk.

- Race: Black men are 60% more likely to develop prostate cancer and have 2-4 times higher death rates from the disease.

- Inherited Mutations: For example, the presence of mutations in BRCA genes, ATM gene, HOXB13, RNase L, and ELAC2 is an indicator for prostate cancer.

- Lifestyle: Diet and obesity may also play a role.

Prostate Cancer Signs and Symptoms

Early prostate cancer often has no symptoms. When they do appear, symptoms may include:

- Difficulty starting and maintaining steady urination

- Frequent urination

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Pain or discomfort during urination

- Erectile dysfunction

Prostate Cancer Screening and Early Detection

Although primary prevention is limited, shared decision-making for PSA-based early detection using risk-adapted strategies is emphasized in NCCN guidelines. Prostate cancer can be detected using:

-

Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test: PSA test is a blood test that measures the levels of PSA, a protein produced by the prostate gland. PSA tests are not always reliable, as levels can also rise due to non-cancerous prostate conditions. This means the test may sometimes produce a false positive, potentially leading to unnecessary and uncomfortable biopsies. Conversely, false negatives can also occur, creating a misleading sense of reassurance. Due to these limitations, there is ongoing debate about whether routine screening ultimately provides more benefit than harm.

-

How often should you get checked for prostate cancer? The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that men between the ages of 55 and 69 make a personal decision about PSA screening in consultation with their doctor. That conversation should take into account things like family history, race, existing health issues, and how a man weighs the pros and cons of possible outcomes.

-

For men 70 and older, the USPSTF recommends against routine PSA screening.

-

-

Digital Rectal Exam (DRE): A digital rectal exam (DRE) is an important test for the early detection of prostate cancer. Because the prostate gland is located where it cannot be felt from outside the body, doctors perform a DRE by gently inserting a lubricated, gloved finger into the patient's rectum to check for lumps, enlargement, or areas of hardness that may be signs of prostate cancer.

-

Prostate Cancer Biopsy: Once PSA tests and a digital rectal exam (DRE) suggest that an individual may have prostate cancer, a core needle prostate biopsy is typically performed. This involves using imaging techniques, such as transrectal ultrasound, MRI, or both, to guide the procedure. A thin, hollow needle is inserted into the prostate either through the rectal wall or through the skin between the scrotum and anus. When the needle is withdrawn, it removes a small cylinder of prostate tissue. This process is repeated several times to collect samples from different areas of the prostate. The biopsy samples are then sent to a laboratory to determine whether they contain cancer cells.

- Talk to your doctor about when screening is right for you. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends shared decision-making beginning at age 50 or earlier for high-risk groups.

Prostate Cancer Treatment Options

Depending on the stage and aggressiveness of the cancer, treatments may include:

1. Active Surveillance: For monitoring low-risk or slow-growing prostate cancer through regular check-ups, PSA tests, and biopsies. Treatment is only initiated if the cancer shows signs of progression. For example, men with localized, low-risk prostate cancer may undergo active surveillance to avoid unnecessary side effects and maintain quality of life.

2. Radical Prostatectomy (Surgery): This involves the surgical removal of the prostate gland, often recommended for those with localized cancer and good overall health. It may be performed via open or laparoscopic surgery. Patients younger than age 70 years with organ-confined prostate cancer are best suited for this treatment option.

3. Radiation Therapy: It uses high-energy radiation to kill cancer cells in the prostate. Two main methods are utilized:

- External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT): Delivers X-rays from outside the body to the prostate.

- Brachytherapy: Radioactive sources ("seeds") are implanted within the prostate.

This treatment is considered suitable for patients who are not eligible for surgical procedures.

4. Cryotherapy: This treatment involves freezing prostate tissue to eradicate cancer cells, using cryoprobes inserted under ultrasound guidance. It is used for localized prostate cancer, especially as an alternative for those unsuitable for surgery or radiation. Complications may include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

5. Hormone Therapy (Androgen Deprivation Therapy, ADT): This treatment is based on reducing androgen (male hormone) levels to prevent them from “fueling” cancer cell growth. This is achieved using medication or surgical removal of the testes, where the hormone is produced. Medications like leuprolide, goserelin, and antiandrogens (flutamide, bicalutamide) can be used. More recently, next-generation androgen receptor pathway inhibitors such as enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide have been introduced. These drugs block androgen signaling more effectively, even in the presence of low testosterone levels, and are often used in advanced or castration-resistant prostate cancer.

6. Chemotherapy: Involves the use of drugs to kill or stop cancer cell growth, especially for advanced or metastatic prostate cancer, or when hormone therapy fails. For example, Docetaxel (Taxotere) is the first-line treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer, while cabazitaxel (Jevtana) is used for docetaxel-resistant cases. Enzalutamide targets the androgen pathway through different mechanisms.

7. Immunotherapy/Biological Therapy: Involves stimulating the immune system to attack cancer cells. This includes vaccines and autologous cell-based approaches. For example, Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is an FDA-approved immunotherapy for advanced and metastatic prostate cancer.

8. Radium-223 Therapy: A Radiopharmaceutical that mimics calcium and is absorbed by cancer cells in bone, delivering targeted radiation. This is used for metastatic prostate cancer that has spread to the bones, reducing pain and risk of fracture.

9. Pluvicto (Lutetium-177–PSMA Therapy): Pluvicto is a targeted radioligand therapy that delivers radiation directly to prostate cancer cells expressing PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen). It combines a radioactive particle (Lutetium-177) with a molecule that binds specifically to PSMA on cancer cells, allowing for precise delivery of radiation while limiting damage to surrounding healthy tissue. Pluvicto is FDA-approved for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) who have previously received hormone therapy and chemotherapy.

10. Combination Therapy: Integrates multiple treatments to improve outcomes and delay resistance. For example, ADT with radiation for high-risk, localized cancer. In several clinical trials, ADT with chemotherapy has been reported to improve survival.

Common Prostate Cancer Myths

-

Myth 1: “Prostate cancer is only an old man's disease.”

- Fact: While most cases are diagnosed in men over 65, younger men can also develop prostate cancer; about 1 in 350 cases are diagnosed before age 50. Men in their 40s and 50s are also at risk, although the risk increases with age.

-

Myth 2 “No family history means no risk.”

- Fact: Though family history increases risk, many men diagnosed have no family history. Having a father with prostate cancer increases your risk, but most men with this history will not get prostate cancer.

-

Myth 3: “No symptoms means no cancer.”

- Fact: Early-stage prostate cancer often has no symptoms. Hence, screening is crucial.

-

Myth 4: “All men with high PSA levels have prostate cancer.”

- Fact: High PSA can be caused by prostate infection, benign enlargement, or inflammation. Further tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis.

-

Myth 5: “Prostate cancer is always fatal.”

- Fact: Most men diagnosed do not die from it. Five-year survival rates are about 98.6%. Many cancers are slow-growing or easily treated, especially if detected early.

-

Myth 6: “PSA tests are routine and always recommended.”

- Fact: PSA tests are not routinely part of annual physicals. Guidelines recommend discussing screening with your doctor based on age and individual risk factors.

Ask an Expert

Have questions about prostate cancer? Submit them to connect with prostate cancer specialists for evidence-based answers tailored to individual risk, values, and goals of care.

Share Your Story

Lived experiences help raise awareness and support others navigating screening, diagnosis, treatment decisions, and survivorship in prostate cancer communities. Interested in sharing your journey? Share your story here .

More Resources

Prostate Cancer in The News

- President Joe Biden’s Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Can It Be Cured?

- What Ryne Sandberg’s Story Reminds Us About Prostate Cancer

Oncoblast Courses

- OncoBlast-GU Oncology II

- OncoBlast-Precision Oncology in GU Cancers: Biomarkers, Sequencing, and Toxicity Management

- OncoBlast-Precision Oncology in GU Malignancies: Applying Biomarkers to Clinical Practice

Patient Resources:

1. Clinical Trials: Staying updated with the latest clinical trials is a great way to take an active role in your care. Discuss with your doctor to determine if you are eligible for certain trials. You may search online databases like ClinicalTrials.gov for trials that align with your condition and location.

2. Online and peer-to-peer support groups: Us Too

3. National organizations that provide resources for prostate cancer patients:

References

- American Cancer Society. (2025, March 21). Tests for prostate cancer. Cancer.org. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-diagnosed.html

- Barr, R. G., Cosgrove, D., Brock, M., Cantisani, V., Correas, J. M., Postema, A. W., Salomon, G., Tsutsumi, M., Xu, H. X., & Dietrich, C. F. (2017). WFUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Ultrasound Elastography: Part 5. Prostate. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 43(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.06.020

- Gann P. H. (2002). Risk factors for prostate cancer. Reviews in urology, 4 Suppl 5(Suppl 5), S3–S10.

- Leslie, S. W., Soon-Sutton, T. L., & Skelton, W. P. (2024, October 4). Prostate cancer. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550/

- Mayo Clinic. (2025, July 19). Types of prostate cancer: Common and rare forms. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prostate-cancer/in-depth/prostate-cancer-types/art-20584938

- Medical News Today. (n.d.). What is the most common age for prostate cancer? https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/age-range-for-prostate-cancer#prevalence-by-age

- National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). SEER cancer stat facts: Prostate cancer. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2025). Prostate Cancer NCCN Guidelines (Version 2.2025) https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1459

- Riesz, M. (Host). (n.d.). Cancer mythbusters: Prostate cancer myths. In Cancer Mythbusters. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. https://www.dana-farber.org/health-library/cancer-mythbusters-prostate-cancer-myths

- Sekhoacha, M., Riet, K., Motloung, P., Gumenku, L., Adegoke, A., & Mashele, S. (2022). Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules, 27(17), 5730. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175730

- Siegel, R. L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H., & Jemal, A. (2025). Cancer statistics, 2025. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 75(1), 10–45. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21871

- UPMC Hillman Cancer Center. (n.d.). Digital rectal examination (DRE) for prostate cancer. https://hillman.upmc.com/cancer-care/prostate/screenings/digital-rectal-exam

Medical Reviewer

Dr. Jordan Ciuro is an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Medical Oncologist with a specialization in genitourinary at Emory Winship Cancer Institute in Atlanta, Georgia. Early in her training, she discovered her passion for medicine and helping vulnerable patient populations, which led her to the AUC School of Medicine, where she completed her medical school training with honors. She then completed her Hematology Oncology Fellowship at Ascension Providence Hospital, Michigan State University, as Chief Fellow. Here, she also completed her Internal Medicine Residency as Chief Resident. She is currently the lead physician preceptor in the fellows oncology clinic at Grady Memorial Hospital and has a passion for teaching and mentoring aspiring students who are underrepresented in the health community. Her interests include writing investigator-initiated trials focusing on healthcare disparities and geriatric survivorship with the aim of tailoring therapy to reduce toxicity and improve patient outcomes and disparities in solid oncology.

Share Article