The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

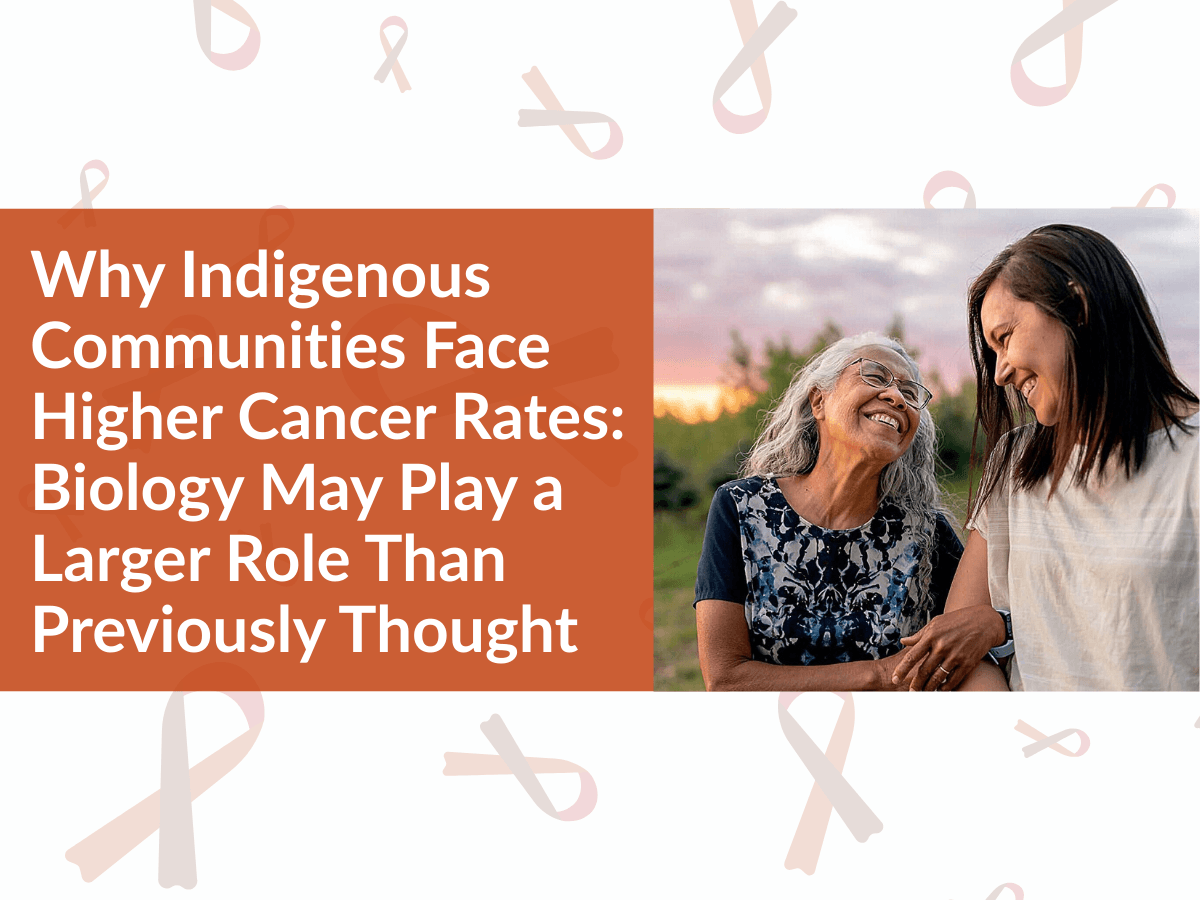

Why Indigenous Communities Face Higher Cancer Rates: Biology May Play a Larger Role Than Previously Thought

Implementation Science & Research Development Officer

Indigenous communities in the United States face some of the highest cancer disparities in the nation, particularly for gallbladder and biliary tract cancers. While overall cancer survival has reached record highs, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander populations continue to experience significantly higher incidence and mortality rates. Emerging research suggests that beyond access and social determinants of health, distinct genetic variants, metabolic pathways, and tumor biology may play a critical role in driving these differences—underscoring the need for precision prevention and equity-focused cancer research.

Last year, as the medical community digested the landmark Cancer Statistics, 2025 report released by the American Cancer Society, the headline became one of national progress. The data show that about 70% of people diagnosed with cancer in the United States are alive five years later, a record high. This continues a 30-year trend of fewer people dying from cancer.

However, beneath this victory lies a widening chasm that will define the next frontier of oncology.

While survival is surging for the general population, Indigenous communities are being left behind. In 2023, the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence launched Project ASIATICA to focus research, policy, and advocacy on the unique needs of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander cancer patients. The latest data reveal that American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations now show the highest incidence rates for liver, kidney, and biliary tract cancers of any racial group in the U.S. In fact, while 71% of the white population survived five years after cancer diagnosis, that number drops to just 62% for the AI/AN community, a gap that research describes as "alarmingly persistent".

This divergence is most lethal in the gallbladder. Gallbladder and biliary tract cancers (GBTC) are rare but highly lethal, with 5-year survival below 20% in most European countries. Their prevalence has risen sharply in recent years, increasing the global health burden. For Alaska Natives and Pacific Islanders, gallbladder cancer (GBC) and bile duct cancer remain an aggressive outlier, driven by two distinct biological engines that recent studies have finally begun to map. While both groups face high mortality, the latest data support a theory of biological divergence.

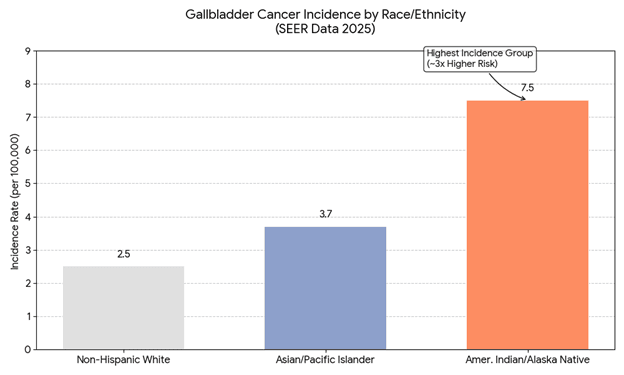

As illustrated by the latest SEER data (Figure 1), the disparity is stark. While the rate of new cases for Non-Hispanic White populations hovers around 2.5 per 100,000, it surges to 7.5 per 100,000 for American Indian and Alaska Native populations, a nearly threefold increase that marks them as the highest-risk group in the nation. For Alaska Natives specifically, the driver is a metabolic "hardware" issue rooted in ancient genetics, whereas for Pacific Islanders, the profile is one of "biological aggressiveness" that strikes early and hard.

Figure 1. Gallbladder Cancer Incidence by Race/Ethnicity based on SEER Data 2025.

For Alaska Native populations, the path to malignancy is frequently paved by a lifelong history of gallstones, or cholelithiasis. The incidence of gallstones in these communities is among the highest in the world, often appearing in children and adolescents. The primary culprit appears to be a genetic "hardware" malfunction involving the liver's transport mechanisms, specifically the ABCG8 gene. A specific variant of this gene, p.D19H, creates a transporter that functions like a pump, pushing cholesterol from the liver into the bile.

In many Alaska Native and Amerindian populations, this pump is genetically "hyperactive," flooding the bile with excess cholesterol to create a supersaturated environment where stones crystallize rapidly. Over decades, these stones cause chronic mechanical irritation and inflammation of the gallbladder mucosa, a process known as the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence, which eventually triggers neoplastic changes, including carcinoma in situ. Evolutionary biologists posit that this variant persists due to the "Thrifty Gene" hypothesis: during the Paleo-Indian migration across the Bering Strait 10,000-50,000 years ago, genetic variants that maximized energy storage provided a survival advantage against harsh winters. In the modern context, however, this mechanism has created a lethal mismatch, predisposing individuals to specific lipid metabolism issues that fuel carcinogenesis.

In stark contrast to this chronic, stone-driven pathway, the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) profile presents a more volatile challenge. The Cancer Statistics, 2025 report and recent disaggregated data have finally "shattered the monolith" of the "Asian/Pacific Islander" category, revealing that NHPI individuals do not just get gallbladder cancer; they get it younger and in more lethal forms. Recent studies highlight that while GBC incidence is stabilizing in some regions, it remains a "substantial and growing burden" in high-risk populations, particularly among older adults in the Asia-Pacific region.

The disparity is profound. New data show that NHPI adults experience significantly higher overall gastrointestinal-related mortality, with disparities most pronounced in liver and bile diseases, often 33% higher than their Asian counterparts. Furthermore, in regions like the Southwest U.S., Native American women face a gallbladder cancer mortality rate that is more than eight times higher than that of white women. This suggests a distinct "biological aggressiveness," potentially driven by unique tumor molecular profiles or epigenetic modifications that drive rapid metastasis. Unlike the slow-burn progression seen in classic stone-associated cancers, the disease in NHPI populations often behaves like a wildfire, severely limiting the window for curative surgical intervention.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for a genetic basis comes from recent admixture mapping studies, which analyze the DNA of populations with mixed heritage to pinpoint disease drivers. Research analyzing the genomic landscape of GBC in patients with Indigenous ancestry, such as the Mapuche, who share genetic lineage with North American Indigenous groups, has found a direct, dose-dependent correlation between ancestry and risk. Researchers have observed that for every 1% increase in Indigenous ancestry, there is a measurable increase in cancer mortality risk, estimated at approximately 3.7%. This strong correlation implicates a concentration of specific "stone-forming" and pro-inflammatory gene variants inherited through Indigenous lineage.

Ultimately, the disparity in gallbladder cancer is not a monolith. For Alaska Natives, the clinical imperative is early surveillance of gallstones to address the "hardware" problem before the irritation turns malignant. For Pacific Islanders, the urgent need is to unravel the molecular drivers of "biological aggressiveness" to develop targeted therapies. As the 2025 data make clear, equity does not mean treating everyone the same; it means recognizing that, while the diagnosis is the same, the genetic and molecular paths traveled by these communities are distinct, and the solutions must be tailored equally.

Works Discussed

- Jennifer J. Gao et al. Advancing Therapies for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Other Pacific Islanders With Cancer: OCE's Project ASIATICA. JCO Oncol Pract 19, 704-705(2023). https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.23.00198

- Siegel, R. L., et al. (2025). "Cancer statistics, 2025." CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 75(1), 10-45. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21871

- ACS Pressroom. ACS Annual Statistics Report: Milestone 70 Percent 5-Year Survival Rate for all Cancers Combined; Largest Gains for Advanced and Fatal Cancers. https://pressroom.cancer.org/cancer-statistics-report-2026

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Minority Health. Cancer and American Indians/Alaska Natives. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/cancer-and-american-indiansalaska-natives

- American Cancer Society Special Report. Special Section: Cancer in the American Indian and Alaska Native Population. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2022/2022-special-section-aian.pdf

- Li, Mingjuan, et al. "Global, regional, and national burden of gallbladder and biliary tract cancer among adults aged 55 years and older, 2010–2021." Frontiers in Nutrition 12 (2025): 1561712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1561712

- Lemrow, S.M., Perdue, D.G., Stewart, S.L., Richardson, L.C., Jim, M.A., French, H.T., Swan, J., Edwards, B.K., Wiggins, C., Dickie, L. and Espey, D.K. (2008), Gallbladder cancer incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives, US, 1999–2004† ‡ §. Cancer, 113: 1266-1273. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23737

- Intercultural Cancer Council, "IC107: Cancer Facts: Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders and Cancer" (2011). Informational and Promotional Materials. 9. https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/info_promo/9

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. (2025). SEERExplorer: Long-Term Trends in Incidence Rates, 2025.* National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html

- Bustos, Bernabé I., et al. "Variants in ABCG8 and TRAF3 genes confer risk for gallstone disease in admixed Latinos with Mapuche Native American ancestry." Scientific reports 9.1 (2019): 772. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-35852-z

- City of Hope. Southwest Native Americans Face High Rates for Some Cancers. May 2025. https://www.cityofhope.org/locations/phoenix/native-american-cancer-rates

- Zollner L, Boekstegers F, Barahona Ponce C, et al. Gallbladder Cancer Risk and Indigenous South American Mapuche Ancestry: Instrumental Variable Analysis Using Ancestry-Informative Markers. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Aug 9;15(16):4033. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37627062/