The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

Cervical Cancer 101

Cervical cancer remains one of the most preventable yet deadly cancers worldwide, and this medically reviewed guide explains its causes, symptoms, prevention strategies, treatment options, and ongoing disparities—helping readers understand how HPV vaccination, screening, and timely care can save lives.

Introduction to Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is a largely preventable cancer of the lower part of the uterus, yet it still causes hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide each year, especially in low- and middle-income countries. This cancer continues to affect certain groups more than others, leading to lower survival rates. Learning about its causes, symptoms, prevention, and treatment can help people protect themselves and support loved ones who may be affected.

What Is Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer develops in the cells lining the cervix, the narrow canal that connects the uterus to the vagina. It is the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in women worldwide. Recent estimates suggest more than 660,000 new cases and about 350,000 deaths in 2022, making it one of the most common cancers affecting women and people with a cervix, with the highest burden in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Latin America, and South‑East Asia. In many high‑income countries, regular screening and vaccination have significantly reduced cervical cancer rates, while in many lower‑income settings, it remains a leading cause of cancer death.

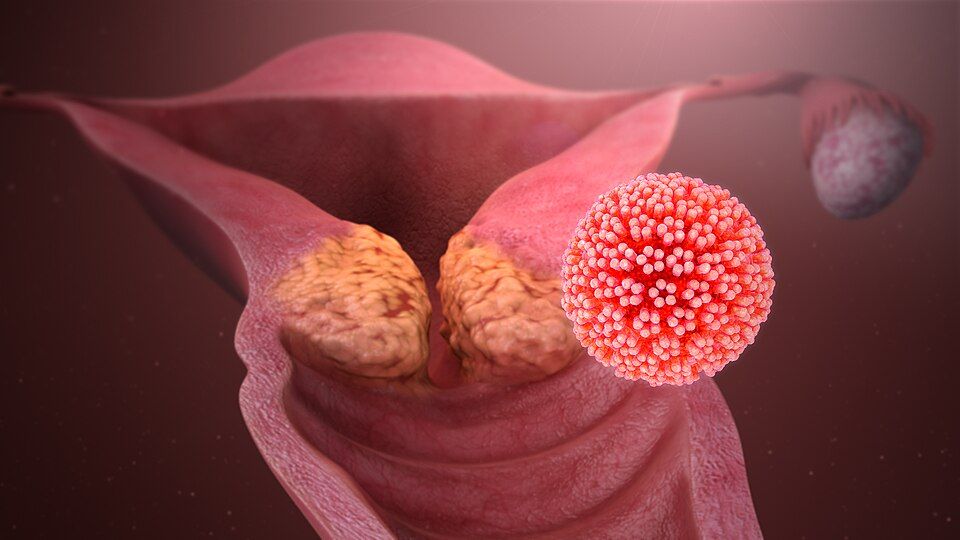

Image illustrating the HPV virus and its link to abnormal cell growth in the cervix

Causes and Risk Factors of Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is often caused by continuous infection with certain “high‑risk” types of human papillomavirus (HPV), a very common sexually transmitted virus. These high-risk types include HPV 16 and HPV 18. Sometimes, most HPV infections clear on their own, but when high‑risk HPV persists for many years, it can damage cervical cells and lead to precancerous changes, and if untreated, cancer develops.

Key risk factors identified in population‑based studies include:

- Early onset of sexual activity and multiple sexual partners increase lifetime exposure to HPV.

- Smoking, which is associated with higher rates of high‑grade cervical lesions and invasive cancer, likely through direct carcinogenic effects and impaired immune clearance of HPV.

- Immunosuppression, including HIV infection and long‑term immunosuppressive therapy, markedly increases both HPV persistence and cervical cancer risk.

- Long‑term use of oral contraceptives has been linked to modestly increased risk in pooled analyses, possibly via hormonal and local immune effects.

- Low socioeconomic status and limited access to screening, which allow precancerous changes to remain undetected and untreated, contribute to later‑stage presentation.

- Genetic susceptibility, co‑infections, and microbiome changes are active areas of research, with molecular and translational studies exploring how host factors influence HPV persistence and transformation of cervical cells.

Types of Cervical Cancer

Most cervical cancers are either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma.

- Squamous cell carcinoma begins in the thin, flat cells covering the outer portion of the cervix and accounts for the majority of cases worldwide, particularly in settings without robust screening.

- Adenocarcinoma starts in the gland‑forming cells of the cervical canal and has become more common over recent decades, partly because it can be harder to detect on traditional Pap cytology.

Other less common cervical cancer types include adenosquamous carcinoma and rare variants such as neuroendocrine (small cell) carcinoma, which often behave more aggressively. Although treatment principles are broadly similar, different histologic types can behave differently and may respond in varying ways to therapy, contributing to differences in outcomes for some groups.

Symptoms of Cervical Cancer

Early cervical cancer and precancerous changes often cause no symptoms, which is why regular screening is so important. When symptoms do appear, they may be subtle at first and can overlap with less serious gynecologic conditions. Common symptoms and signs include:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as bleeding after sexual intercourse, between periods, or after menopause

- Unusual vaginal discharge that may be watery, bloody, or have a strong odor

- Pelvic pain or pain during sexual intercourse

In more advanced disease, symptoms can include difficulty urinating, blood in urine, constipation, back or leg pain, or swelling of the legs if the cancer presses on nerves or blood vessels.

Anyone experiencing these symptoms, especially if they persist, should seek prompt medical evaluation, even if they are up to date with screening.

Can Cervical Cancer Be Prevented? Tips for Early Detection and Risk Reduction

Cervical cancer can be largely prevented through HPV vaccination and high‑quality screening. In fact, the combination of primary prevention (vaccines) and secondary prevention (screening and treatment of precancer) has led some high‑income countries to project eventual elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem.

Some evidence-based strategies for prevention and early detection of cervical cancer include:

- HPV vaccination: Vaccines that protect against high‑risk HPV types (including 16 and 18, which cause most cervical cancers) are recommended for preteens and can be given up to young adulthood, with some countries adopting one‑dose schedules after evidence of strong protection.

- Cervical screening: Depending on the country, screening may use HPV testing, Pap tests (cytology), or co‑testing at regular intervals, starting in early adulthood and continuing until mid‑ or later life; screening can detect precancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) that can be treated before it progresses.

- Safe sexual practices: Condom use and delaying the onset of sexual activity may lower HPV transmission risk, though they do not eliminate it.

- Smoking cessation: Quitting smoking reduces cervical cancer risk and improves overall health.

The World Health Organization (WHO)’s cervical cancer elimination initiative is a widely discussed topic in global oncology. It sets targets for HPV vaccination, screening coverage, and timely treatment of precancer and cancer by 2030, reflecting a consensus that cervical cancer can be prevented and controlled on a population level.

Cervical Cancer Treatment: Options, Advances, and What to Expect

Treatment recommendations for cervical cancer are grounded in clinical trials, large observational cohorts, and consensus guidelines from groups such as the NCCN and international gynecologic oncology societies. Management is tailored to stage, tumor size, and histology, nodal status, fertility goals, comorbidities, and access to specialized care, and is best coordinated by a multidisciplinary team.

Main treatment approaches include:

- Surgery: For very early‑stage disease, options can range from removal of a small part of the cervix (conization) or fertility‑sparing procedures (such as trachelectomy) to hysterectomy with removal of nearby lymph nodes.

- Radiation therapy: External beam radiation combined with internal radiation (brachytherapy) is a standard treatment for many locally advanced cancers and may be used after surgery to prevent relapse if high‑risk features are present.

- Chemoradiation: Concurrent chemotherapy given with radiation improves survival in many patients with locally advanced disease by sensitizing the tumor to radiation.

- Systemic therapy for recurrent or metastatic disease: Options may include chemotherapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapies in selected patients, reflecting recent updates in major guidelines.

Supportive care to manage symptoms, address side effects, preserve sexual health and fertility when possible, and provide psychological and social support is an essential part of comprehensive cervical cancer care

Disparities in Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer shows significant disparities in who it affects and in patient outcomes across different populations and regions. In low‑ and middle‑income countries (LMICs), where HPV vaccination and screening coverage are often low, and gynecologic oncology services may be limited, cervical cancer accounts for the vast majority of related deaths worldwide.

Within high‑income countries, studies show that racial and ethnic minorities, rural populations, uninsured or underinsured individuals, and those with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages and to experience worse outcomes. For example, US registry studies have documented higher incidence and mortality among Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaska Native women, and disparities in histologic subtypes and treatment patterns even after adjusting for stage.

Multiple drivers of these inequities include:

- Structural factors: limited access to primary care, gynecologic specialists, and radiotherapy; transportation barriers; and fragmented referral systems.

- Financial and insurance barriers: out‑of‑pocket costs and lack of coverage impede vaccination, screening, and timely treatment.

- Sociocultural and historical issues: stigma surrounding sexual health, language barriers, and mistrust of medical institutions can reduce engagement with preventive services.

Interventions for cervical cancer are gradually being implemented in communities facing these barriers. These include expanding school‑based HPV vaccination, integrating cervical screening into primary care and HIV services, deploying self‑sampling HPV tests, strengthening referral pathways for abnormal results, and ensuring guideline‑concordant chemoradiation and palliative care in underserved communities.

Ask An Expert

Have questions about cervical cancer? Submit them to connect with cervical cancer specialists for evidence-based answers tailored to individual risk, values, and goals of care.

Share Your Story

Lived experiences help raise awareness and support others navigating screening, diagnosis, treatment decisions, and survivorship in cervical cancer communities. Interested in sharing your journey? Share your story here.

More Resources

Continuing Medical Education

Top Organizations Advancing Cervical Cancer Advocacy

- Binaytara Center for Women's Cancer Access and Advocacy (https://binaytara.org/center-for-women-cancer)

- Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) (https://uicc.org)

- International Gynecologic Cancer Society – IGCS / IGCAN (https://igcs.org/igcanetwork)

- Grounds for Health (https://groundsforhealth.org)

- TogetHER for Health (https://togetherforhealth.org)

- National Cervical Cancer Coalition (NCCC) (https://www.nccc-online.org)

- HPV Prevention and Control Board (https://www.hpvboard.org)

- Global Initiative Against HPV and Cervical Cancer (GIAHC) (https://giahc.org)

- Prevent Cancer Foundation (https://preventcancer.org)

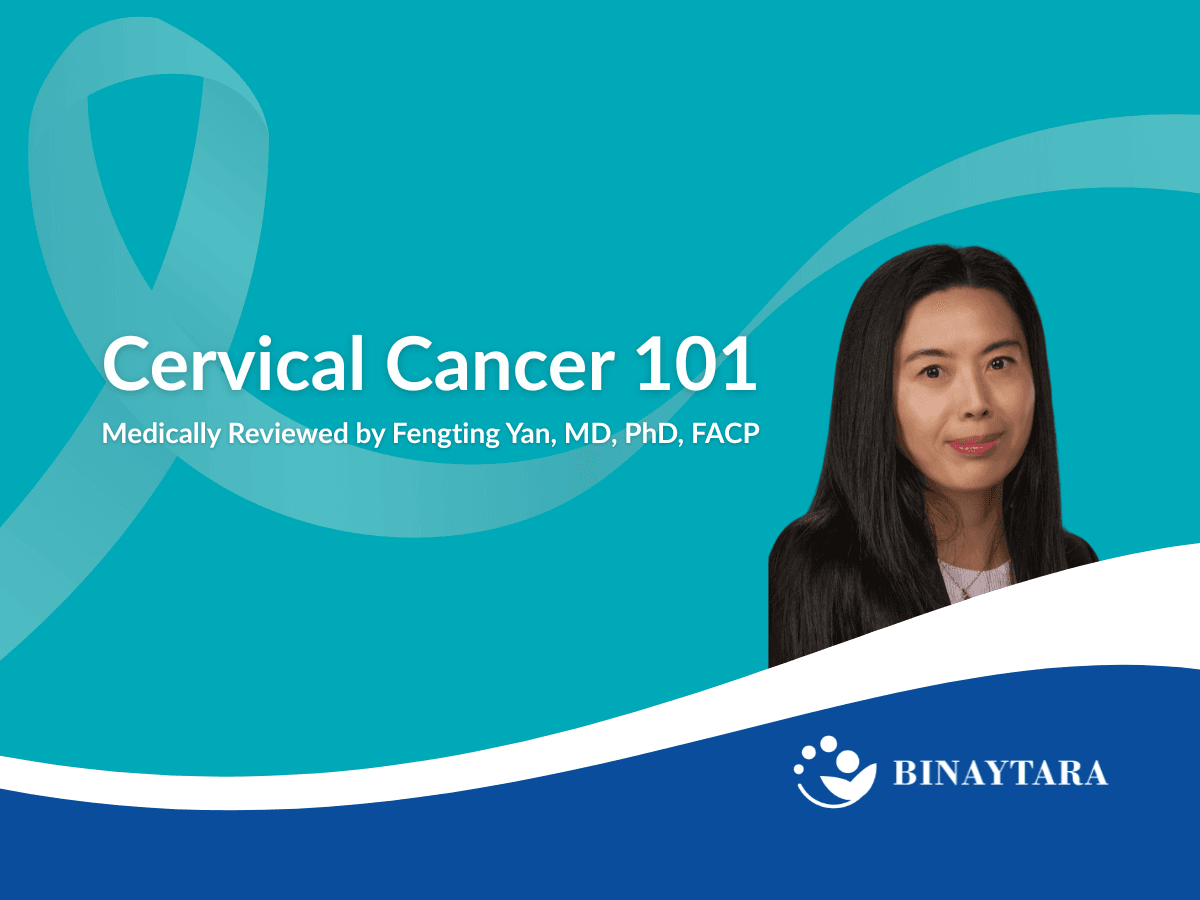

Medical Reviewer

Dr. Fengting Yan is a breast medical oncologist at the True Family Women’s Cancer Center, Swedish Cancer Institute in Seattle. Dr.Yan completed her fellowship in hematology/oncology at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington. Dr. Fengting Yan brings a rich background in translational research, women’s health education, and global clinical training. Dr. Yan's work focuses on identifying molecular targets and advancing therapies in women’s cancers. As an editor for Binaytara's International Journal of Cancer Care and Delivery (IJCCD), Dr. Fengting Yan helps shape discourse at the intersection of research and patient care. Dr. Yan is also a co-chair of the Binaytara Education Committee.

References

- Abu-Rustum, N. R., Yashar, C. M., Arend, R., Barber, E., Bradley, K., Brooks, R., Campos, S. M., Chino, J., Chon, H. S., Crispens, M. A., Damast, S., Fisher, C. M., Frederick, P., Gaffney, D. K., Gaillard, S., Giuntoli, R., Glaser, S., Holmes, J., Howitt, B. E., Lea, J., … Espinosa, S. (2023). NCCN Guidelines® insights: Cervical cancer, Version 1.2024. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 21(12), 1224–1233. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0062

- Fowler, J. R., Maani, E. V., Dunton, C. J., et al. (2025). Cervical cancer. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431093/

- Hakim, R. U., Amin, T., & Ul Islam, S. M. B. (2025). Advances and challenges in cervical cancer: From molecular mechanisms and global epidemiology to innovative therapies and prevention strategies. Cancer Control, 32, 10732748251336415. https://doi.org/10.1177/10732748251336415

- National Cancer Institute. (2022). Cervical cancer causes, risk factors, and prevention. https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/causes-risk-prevention

- Naslazi, E., Hontelez, J. A. C., Naber, S. K., van Ballegooijen, M., & de Kok, I. M. C. M. (2021). The differential risk of cervical cancer in HPV-vaccinated and -unvaccinated women: A mathematical modeling study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 30(5), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1321

- Neibart, S., Zhou, N., Chino, J., Earles, T., Teoh, D., Pinder, L. F., Pierce, J. Y., Olawaiye, A., Leath, C. A., Einstein, M. H., et al. (2025). Health equity, disparities, and barriers to cervical cancer care in the U.S.: A consensus statement by SGO, ACOG, ASCCP, ASTRO, and ABS addressing the WHO cervical cancer elimination campaign goals related to treatment. Gynecologic Oncology, 200, 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2025.07.029

- World Health Organization. (2025). Cervical cancer (fact sheet). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer