The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

How Medical Oncologists Select Targeted Therapies for Breast Cancer ESR1 and Pancreatic MTAP Mutations

Precision oncology is reshaping cancer care—but translating biomarkers into real-world treatment decisions remains complex. In this tumor board–style session from the Precision Oncology Summit, medical oncologists explore how ESR1 mutations in metastatic breast cancer and MTAP deletions in pancreatic adenocarcinoma guide therapy selection, sequencing, and quality-of-life–centered care.

Pictured from left to right: Dr. Mark Pegram, Dr. Milana V. Dolezal, Dr. Shruti Rajesh Patel, Dr. Surbhi Singhal, and Dr. Varun Monga

This video shows a tumor board-style presentation at the Precision Oncology Summit, highlighting expert perspectives on ESR1 mutations in metastatic breast cancer, MTAP-deleted pancreatic adenocarcinoma, KRAS G12C Mutation, and EZH2 Mutation in Sarcoma. Real-world cases that illustrate the evolving landscape of biomarker-driven therapy were also discussed.

The session was chaired by Dr. Mark Pegram (Stanford Medicine), featuring Dr. Milana V. Dolezal (Stanford Medicine), Dr. Shruti Rajesh Patel (Stanford Medicine), Dr. Surbhi Singhal (UC Davis Health), and Dr. Varun Monga (UCSF Health).

The transcript below has not been reviewed by the speakers and may contain errors.

Dr. Milana Dolezal on ESR1 Mutations in Metastatic Breast Cancer

Dr. Melana Dolezal, clinical associate professor at Stanford School of Medicine in the Division of Oncology, presented cases highlighting the evolution of ESR1 mutation management in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. With extensive experience in research and drug development, she framed the discussion around two complex patients whose journeys illustrate the challenges of bone-only disease, circulating tumor DNA testing limitations, and the timing of targeted therapies.

Case 1: Sixteen Years of Hormone Receptor-Positive Disease

The first patient was initially diagnosed in the early 2000s with early-stage estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer. She received an aromatase inhibitor for approximately five years. In 2009, she presented with bone pain and was diagnosed with bone-only metastatic breast cancer. At that point, treatment was initiated with fulvestrant (the "butt shots," as referenced colloquially), a selective estrogen receptor degrader, in addition to bone-targeted agents.

She maintained stable disease for quite some time. With the approval of palbociclib in 2015, the CDK4/6 inhibitor was added to her regimen while still in the first-line setting. This combination continued successfully until 2021, when she began experiencing fatigue, anemia, and nonspecific symptoms.

Imaging revealed hydronephrosis. Given the nature of lobular breast cancers—which can be "sticky" and infiltrative even without obvious peritoneal disease—this finding was suspected to be disease-related. Treatment was switched to abemaciclib at that point.

Guardant NGS testing performed on blood at that time returned negative. This finding underscores a critical principle: negative circulating tumor DNA does not mean definitively negative. Rather, it is inconclusive and limited by the sensitivity of the assay. Patients with bone-only disease and low tumor burden may not have sufficient tumor shedding into circulation to be detected by current NGS sensitivity thresholds, particularly compared to tumor-informed circulating tumor DNA platforms like Natera.

To investigate the anemia further, bone marrow biopsies were performed to rule out marrow infiltration. These biopsies were negative, and repeat testing of the marrow also showed no evidence of disease. The patient continued on abemaciclib and eventually was switched to elacestrant.

By this point, blood testing had revealed an ESR1 mutation. However, elacestrant—which would later be approved based on the EMERALD trial—was not yet available. This case illustrates a critical clinical reality: not only does cancer evolve biologically, acquiring mutations over time, but clinicians are also at the mercy of which drugs have regulatory approval at any given moment.

The patient was also crossing a tipping point toward endocrine insensitivity. It is well established that as patients progress through multiple lines of therapy and begin receiving chemotherapy, their disease often becomes less endocrine-sensitive over time.

On elacestrant, she did not have a particularly long treatment duration and eventually progressed. Out of curiosity, a Cerianna PET scan was performed several months into elacestrant therapy to assess whether additional hormone sensitivity might be present. The scan showed some estrogen receptor uptake in the bones, even after fulvestrant exposure. It is worth noting that fulvestrant can irreversibly affect the estrogen receptor and potentially create false-negative Cerianna PET results, though in this case there had been many months between fulvestrant and the imaging.

Ultimately, the patient was started on trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd). She had baseline renal insufficiency, which retrospectively represented a setup for interstitial lung disease risk. After over a year on T-DXd—during which she did not feel particularly well—she developed ILD at approximately 15 months and decided to transition to hospice.

Remarkably, she experienced a durable remission. Fifteen months later, her disease was stable, and she wanted to discontinue hospice. At that point, elacestrant had been approved. She was started on it and tolerated it reasonably well, experiencing only mild nausea.

Eventually, however, her disease accelerated. She developed a PI3-kinase mutation, additional ESR1 mutations, and new bone and liver metastases. Treatment was then transitioned based on the PI3-kinase mutation to a combination the patient affectionately called "true crap" due to significant diarrhea—likely referring to a PI3K inhibitor-containing regimen.

This 16-year trajectory illustrates not only the biological evolution of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer but also the practical constraints imposed by the timing of drug approvals. The patient's toolbox expanded with successive approvals—palbociclib, abemaciclib, elacestrant—but not always when they could be optimally employed. The disease eventually shifted into a more hormone-insensitive phenotype, reflected in both clinical behavior and genomic changes.

Genomically, the patient's initial NGS showed a low circulating tumor DNA fraction with an ESR1 mutation. She had bilateral hydronephrosis and was on elacestrant at that time. Less than a year later, her disease burden increased significantly. She acquired additional mutations, including a PI3-kinase mutation and more ESR1 mutations, with a much higher tumor fraction and elevated variant allele frequencies.

Defining Hormone Sensitivity and Treatment Selection

This case raises critical clinical questions that community oncologists face regularly. How do we define hormone sensitivity? What is the tipping point at which disease becomes hormone-refractory? While there is a clinical gestalt—for instance, a patient with one new bone lesion and no visceral disease might still be considered endocrine-sensitive—clear definitions remain elusive.

Second-line and beyond treatment strategies should be biomarker-driven. But what about co-mutations? PI3-kinase and ESR1 mutations can both be present. Does PI3K "trump" ESR1, or vice versa? The answer likely depends on the clinical picture: where the disease is located, the burden, and the pace of progression.

Duration of first-line CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy also predicts hormone sensitivity. Patients who remain on a CDK4/6 inhibitor for more than 12 or 18 months in the first-line setting tend to retain greater endocrine sensitivity in subsequent lines.

The field has definitions of clinical primary and secondary resistance, as well as molecular definitions. However, as this case illustrates, ESR1 mutations can be acquired over time or may be present subclinically and undetectable in blood initially. Approximately 40 percent of metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancers develop ESR1 mutations over time. Similarly, alterations in the PI3-kinase pathway—whether AKT, PI3K, or mTOR—are found in about 40 percent of cases. Unlike ESR1, these mutations are not always acquired; they can be present at baseline as well.

The EMERALD Trial: First Oral SERD Approval

Elacestrant was the first oral selective estrogen receptor degrader on the market. The EMERALD trial evaluated patients who had relapsed or progressed after at least one line of endocrine therapy in the hormone receptor-positive metastatic setting. Importantly, all patients were required to have received a CDK4/6 inhibitor, which becomes relevant when examining who actually benefited from the drug.

The primary endpoint was progression-free survival, comparing the oral SERD (eliminating the need for intramuscular fulvestrant injections) to the standard of care. The FDA approved elacestrant in January 2023 based on the ESR1-mutant population.

The devil is in the details of the survival curves. In the entire population, the curves drop off very rapidly within the first three months. These early progressors were typically patients who had only been on a CDK4/6 inhibitor for approximately six months—the "bad actors" with rapid endocrine resistance. In this group, the standard of care progression-free survival was about 1.9 months versus 4 months with elacestrant.

However, patients who had been on a first-line CDK4/6 inhibitor for at least 12 or 18 months derived much more substantial benefit. In the ESR1-mutation population with prolonged first-line CDK4/6 inhibitor exposure, progression-free survival was 8.5 months versus 1.9 months—a clinically meaningful difference.

Bone-only patients appeared to do somewhat better. Those with visceral disease had less impressive outcomes, though the numbers in these subgroups were small. The trial did include patients with co-mutations as well. The EMERALD trial taught the field important lessons about trial design, particularly regarding patient selection and duration of prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy. These lessons informed subsequent studies, including SERENA-6.

EMBER-3 Trial: A Second Oral SERD

Lulestrant, a second oral SERD, was FDA approved on September 25th based on the monotherapy arm of the EMBER-3 trial. The drug name sounds like something from Harry Potter, as noted during the presentation.

Arm A of EMBER-3 compared lulestrant monotherapy to the standard of care. This was a slightly different population from EMERALD: not all patients were required to have received a CDK4/6 inhibitor, though most did. Most had received palbociclib, which was fortunate for a third arm (Arm C) that was added later with 213 patients. Data from that arm continues to evolve.

The primary endpoint was progression-free survival. FDA approval was based on PFS improvement: 5.5 months with lulestrant versus 3.8 months with standard of care, with a hazard ratio of 0.62.

A Crowded Treatment Landscape

The ESR1-targeted space is becoming crowded. EMBER-3 demonstrated monotherapy efficacy for lulestrant. Data from Arm C will continue to mature. Other agents are in development, including PROTACs (proteolysis-targeting chimeras), though time did not permit detailed discussion of those approaches.

Cross-trial comparisons are always cautioned against, yet clinicians inevitably make them when trying to decide which agent to use. The field is beginning to resemble multiple myeloma, with triplet and quadruplet combinations emerging. Some clinicians may remember the days when megestrol acetate was used not just as an appetite stimulant but as active therapy in breast cancer.

Combination regimens are now the focus. The ELEVATE study continues enrolling, with data presented at ASCO showing elacestrant combinations. Interestingly, data are emerging regardless of ESR1 mutation status—a trend also seen in EMBER-3. Progression-free survival appears consistent at around 8.3 months across various combinations.

The everolimus-containing arms recall the earlier BOLERO data, with associated toxicities like mouth sores and stomatitis that can be mitigated with steroid mouthwashes. Safety data from the combinations, presented by Nancy Chen, show toxicity profiles consistent with what would be expected from the individual agents.

AVERO Trial: Recent ESMO Data

The AVERO trial was presented just days before this session at ESMO in Germany. In the ESR1-mutation population, the combination of girodestrant and everolimus showed a progression-free survival of approximately 9.9 months versus just over 5 months with standard therapy. However, this came at the cost of 19 percent grade 3 stomatitis—an expected toxicity from mTOR inhibitors, but still a significant burden.

For bone-only hormone receptor-positive patients, the best opportunity remains the first-line CDK4/6 inhibitor-based regimen, where treatment can be extended for many years. The first patient discussed was on essentially the same combination for almost a decade. Once the disease progresses into the second and third lines, the arrows become shorter. The benefit from each subsequent therapy diminishes—there is less "bang for the buck."

Surveillance Strategies and Blood-Based Biomarkers

How should clinicians monitor these patients? When can we predict that a patient will become a "bad actor," shifting toward endocrine refractoriness and hormone insensitivity? Blood-based markers are not new concepts. Some community oncologists still use traditional tumor markers like CA 15-3 or CA 27-29 when they are helpful. However, current methods cannot detect micrometastatic disease, and they have significant limitations.

Newer technologies offer potential advantages: tumor-informed circulating tumor DNA platforms that track patient-specific mutations, or uninformed NGS approaches that examine variant allele frequencies. However, a reminder from 2012 is relevant: Dan Hayes conducted work with circulating tumor cells in the SWOG trial, which evaluated changing chemotherapy regimens based on molecular evidence of resistance. That trial was negative—a cautionary tale about acting on biomarker changes without validated clinical benefit.

Case 2: ESR1 Mutation Detected Before Radiographic Progression

The second case involved a 57-year-old woman diagnosed in 2010 with high-risk, node-positive (N3) stage III estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. She received chemotherapy followed by 10 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy, including both tamoxifen and an aromatase inhibitor. After completing the 10-year mark, she was discharged to primary care follow-up.

Three years later, she presented with back pain. Imaging revealed a T10 lesion, which was biopsied and confirmed to be estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor-positive disease. PET imaging did not show distant metastases beyond this site. She was started on first-line therapy for hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer with ribociclib, fulvestrant, and denosumab.

Guardant testing at that time showed both an ESR1 mutation and a PIK3CA mutation already present. However, the standard of care at that point was to initiate first-line CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy. Starting with elacestrant in the first line would not have been appropriate based on available evidence.

She did well on this regimen for some time. At her most recent check, circulating tumor DNA levels were low. Monitoring frequency typically includes circulating tumor DNA testing approximately twice per year and PET scans every four to six months, though this varies based on disease burden, patient symptoms, and laboratory findings.

Unfortunately, a recent scan showed a new liver lesion. Workup was pending at the time of presentation. The clinical question became: what should be done next? She has had a good duration of response to CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy—certainly greater than 12 months. Should elacestrant be started now? Should one wait for combination data to mature? Should treatment target the PI3-kinase mutation instead?

PADA-1 Trial: Treating Molecular Resistance

The PADA-1 French trial specifically addressed the question of molecular resistance. Patients were on first-line aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib therapy and were screened at baseline, one month, and every two months for ESR1 mutations using circulating tumor DNA. Patients who developed an ESR1 mutation were randomized either to switch to fulvestrant with palbociclib or to continue their current regimen.

A progression-free survival benefit was observed with switching, including a PFS2 benefit (progression-free survival from randomization until progression on the next line of therapy). However, the magnitude of PFS2 benefit depends on what patients receive after they progress from PFS1, which limits interpretation.

Nevertheless, PADA-1 set the stage for SERENA-6, a larger trial exploring this micrometastatic concept—treating molecular recurrence before radiographic progression becomes evident.

SERENA-6 Trial: Switching Therapy at ESR1 Emergence

SERENA-6, presented by Dr. Turner at ASCO, evaluated switching therapy upon emergence of an ESR1 mutation, before radiographic progression. Patients had all been on an aromatase inhibitor and CDK4/6 inhibitor for at least six months—a requirement based on EMERALD trial findings that showed early progressors (those on CDK4/6 inhibitors for only about six months) had poor outcomes.

The trial randomized approximately 300 patients at the point of ESR1 mutation emergence to either switch to the oral SERD camizestrant or continue current therapy. Importantly, while six months was the minimum duration of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, most patients had been on treatment for nearly two years, with some having received it for up to 96 months. This prolonged exposure is highly relevant when interpreting the results.

The primary endpoint was progression-free survival, but in the stage IV metastatic setting, quality of life may be equally or more important clinically. Patients who switched to camizestrant did show an improvement in time to deterioration of quality of life. It would be valuable to see breakdowns by specific quality-of-life domains, particularly pain, as patients sometimes recognize disease progression before imaging does, experiencing symptoms like increasing pain.

There are ongoing controversies around what progression-free survival truly means in this context. Also important is what patients received as subsequent therapy. Many received chemotherapy in the second-line setting, which might not reflect current practice patterns. Others received antibody-drug conjugates and other newer agents.

Unanswered Questions in ESR1-Mutant Disease

These two cases frame the evolution occurring in this field and highlight several unresolved questions. How can endocrine sensitivity be better refined and defined for the patient sitting in front of you? What is the next appropriate step in sequencing therapy?

How do practice-changing data and the timing of FDA approvals influence the therapeutic toolbox available at critical decision points? Which oral SERD should be selected now that two are approved? Combinations are clearly on the horizon. Clinicians should be mindful of incremental benefits—a hazard ratio of 0.38 is far more compelling than 0.65.

Regarding surveillance: what is the optimal approach? Typically, repeat NGS would be performed at progression. But should testing now occur every three months? Should a full NGS panel be ordered, or only ESR1-specific testing? Will insurance cover frequent comprehensive genomic profiling? The principle of "choosing wisely" becomes relevant.

The best shot on goal remains maximizing the duration of first-line therapy. Do time-to-deterioration endpoints truly improve patient experience? What additional data are needed before switching therapy in the absence of radiographic confirmation of progression feels comfortable in routine practice?

These questions remain open and will be critical to address as the field moves forward with molecularly directed therapy in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Dr. Shruti Patel on MTAP-Deleted Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Dr. Shruti Patel, clinical assistant professor of medicine in the Early Drug Development Program at Stanford University and a medical oncologist at the VA Palo Alto, presented on MTAP-deleted pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Specializing in GI cancers, she leads initiatives to expand clinical trial access for veterans and underserved populations and is a recipient of the Stanford Cancer Institute Innovation Award. She serves on the board of directors of the Association of Northern California Oncologists.

MTAP deletion represents a rare but not insignificant actionable subset of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma that is beginning to shift how clinicians think about molecularly defined therapy in this disease, beyond KRAS.

Case Presentation: An 84-Year-Old with Pancreatic Cancer

The patient was an 84-year-old gentleman with a remote history of resected stage I colon cancer in 2000. He presented to the emergency department with jaundice and pale stools. Imaging revealed a 2.6 by 2.2 centimeter mass in the pancreatic head.

His family history was notable for a mother with breast cancer at age 45 and a maternal aunt with breast cancer at age 50. This represents a relatively classic presentation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with some family history suggesting possible genetic predisposition, though nothing definitive.

He underwent surgical resection, which confirmed moderately differentiated pancreatic adenocarcinoma with perineural invasion and one out of 45 lymph nodes positive. He was staged as IIB (T2, N1, M0). The tumor was mismatch repair proficient. Germline testing—which should be performed for all patients with pancreatic cancer regardless of family history—showed no pathogenic variants.

He received adjuvant gemcitabine monotherapy due to his postoperative functional status, rather than more intensive regimens like gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel or FOLFIRINOX. He tolerated this well and felt good during surveillance.

Approximately 10 months later, a CT scan showed a 3.0 by 2.3 centimeter mass in the surgical bed encasing the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, and common hepatic artery. Additionally, there was a 3.4 by 2.7 centimeter mass in the right hepatic lobe.

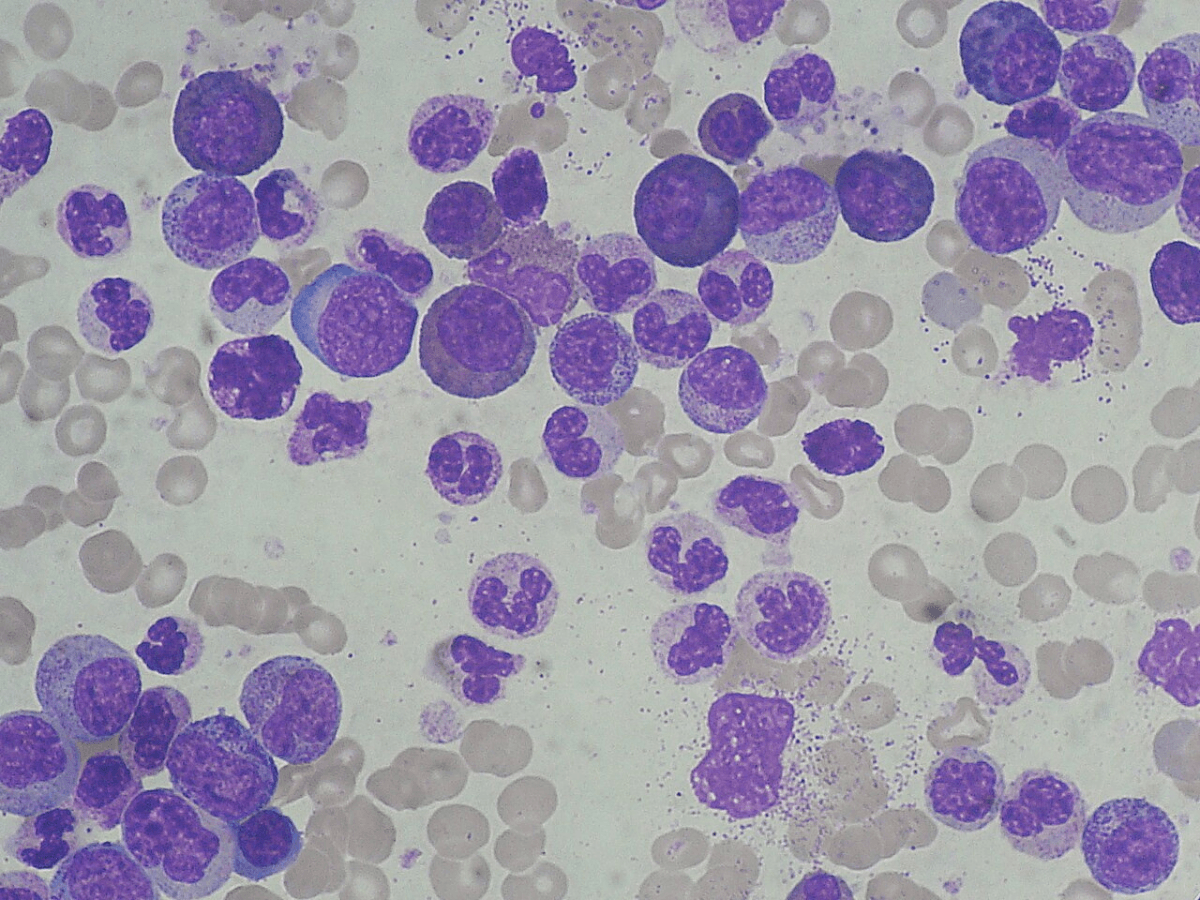

At this juncture, the question becomes: what can tumor biology tell us? Historically, with pancreatic cancer, the answer was very little. He was not an ideal candidate for intensive chemotherapy, having received only single-agent gemcitabine in the adjuvant setting. Next-generation sequencing was performed, as it should be for all metastatic pancreatic cancer patients.

Testing revealed a KRAS G12D mutation, which is potentially actionable if clinical trials are available. More importantly for this discussion, the report also showed CDKN2A and CDKN2B mutations. Why does this matter?

The Biology of MTAP Deletion and Synthetic Lethality

CDKN2A and CDKN2B are located on chromosome 9p21. MTAP sits immediately adjacent to them. Approximately 40 percent of patients with CDKN2A mutations will also have MTAP loss due to this physical proximity—a phenomenon called co-deletion.

It is critical that when a CDKN2A mutation appears on a report, clinicians verify that the testing platform specifically assessed for MTAP loss and that this result is clearly reported. Not all NGS platforms routinely report MTAP status, though more are beginning to include it as the clinical relevance becomes better recognized.

What does MTAP loss mean functionally? MTAP normally breaks down MTA (methylthioadenosine). When MTAP is deleted, MTA accumulates in the cell. Accumulated MTA inhibits another enzyme called PRMT5. PRMT5 is essential for normal cellular function in cancer cells.

In MTAP-deleted cells, there is a high MTA concentration and PRMT5 is already partially inhibited. Drug developers recognized an opportunity: what if PRMT5 could be inhibited further? Could this push the cell past a threshold where it can no longer survive?

This is the principle of synthetic lethality. The tumor has one defect (MTAP loss). A drug exploits a complementary vulnerability (PRMT5 dependence) to selectively kill cancer cells while sparing normal cells that have intact MTAP.

PRMT5 inhibitors exist in first-generation and second-generation forms. Second-generation inhibitors are specifically designed to bind PRMT5 more effectively in an MTA-rich, MTAP-deficient environment, making them selectively lethal to MTAP-deleted tumors. This represents an incredibly elegant application of biological knowledge to drug discovery—using the tumor's own vulnerabilities against it.

MTAP deletion is not unique to pancreatic cancer. The prevalence is substantial across multiple malignancies. In thoracic oncology, pleural mesotheliomas and non-small cell lung cancers harbor MTAP deletions. In genitourinary cancers, urothelial carcinoma shows significant rates. Glioblastoma has MTAP deletion in 40 to 60 percent of cases—a very high prevalence.

Treatment Decision: Chemotherapy or Targeted Therapy?

Returning to the patient, two options were considered. Option A was the familiar path: FOLFIRINOX or modified FOLFIRINOX, which could potentially achieve cytoreduction. However, he was 84 years old and had been deemed unable to tolerate gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel or full FOLFIRINOX in the adjuvant setting. Intensive chemotherapy raised significant concerns.

Option B was an MTA-cooperative PRMT5 inhibitor in a phase I-II clinical trial. The advantages: it is an oral daily pill, it is targeted therapy exploiting a specific vulnerability. The disadvantages: it is an early-phase study with a less well-characterized toxicity profile, and efficacy data are limited.

After thorough discussions with the patient and his family, they proceeded with enrollment in the phase I-II trial.

Treatment Response and Quality of Life

His first two scans on therapy showed gradual tumor shrinkage, though this was still officially categorized as stable disease per RECIST criteria. Subsequent scans continued to show benefit.

Most importantly, the patient was able to attend his granddaughter's wedding with minimal side effects. He experienced fatigue and grade 1 anemia—manageable toxicities. It is questionable whether he would have been able to travel and attend the wedding had he been receiving FOLFIRINOX or modified FOLFIRINOX, given the typical toxicity profile of those regimens.

This quality-of-life consideration is profound. For an 84-year-old patient with metastatic disease, the ability to maintain function and participate in meaningful life events may be as important as—or more important than—maximal tumor response.

Toxicity Profile of PRMT5 Inhibitors

First-generation PRMT5 inhibitors had considerable hematologic toxicity—anemia and thrombocytopenia, often grade 3, which limited their clinical utility. This drove development of second-generation agents with improved therapeutic windows.

Second-generation PRMT5 inhibitors still require monitoring for anemia and thrombocytopenia, but rates of severe cytopenias are reduced. Other side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, altered taste, and alopecia. A common constitutional symptom is fatigue.

The key management principles are proactive monitoring of hematologic parameters and aggressive GI symptom management—though admittedly, proactive GI management should be standard for any regimen in pancreatic cancer patients.

Conclusion

This molecular tumor board session highlighted two molecularly defined scenarios that illustrate both the promise and challenges of precision oncology. ESR1 mutations in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer demonstrate how biomarker-driven therapy is evolving rapidly, with multiple oral SERDs now approved and combinations under investigation. However, clinical implementation remains complex, requiring integration of tumor biology, treatment history, co-mutations, and the practical realities of drug availability and approval timing.

The MTAP-deleted pancreatic cancer case represents an emerging frontier where synthetic lethality offers hope in a disease with historically limited targeted therapy options. The elegant biology underlying PRMT5 inhibition in MTAP-deficient tumors demonstrates how deep understanding of cancer vulnerabilities can translate into meaningful clinical opportunities—particularly when quality of life and tolerability are paramount considerations.

Both cases underscore that precision oncology is not merely about identifying mutations but about thoughtfully integrating molecular information into clinical decision-making, always keeping the patient's goals and quality of life at the center of care.