The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

Liquid Biopsy in Oncology: What Clinicians Are Actually Saying

Liquid biopsy has rapidly moved from a research tool into routine oncology practice—but knowing when and how to use it remains complex. In this expert panel discussion from the Precision Oncology Summit, leading clinicians and researchers explore the real-world role of circulating tumor DNA testing, comparing liquid biopsy with tissue biopsy, examining challenges such as clonal hematopoiesis and variant allele fraction interpretation, and discussing where tumor-informed assays and minimal residual disease testing are truly changing patient care. Drawing on evidence from colorectal, prostate, bladder, and other cancers, the panel offers practical insights to help clinicians navigate the evolving landscape of precision oncology.

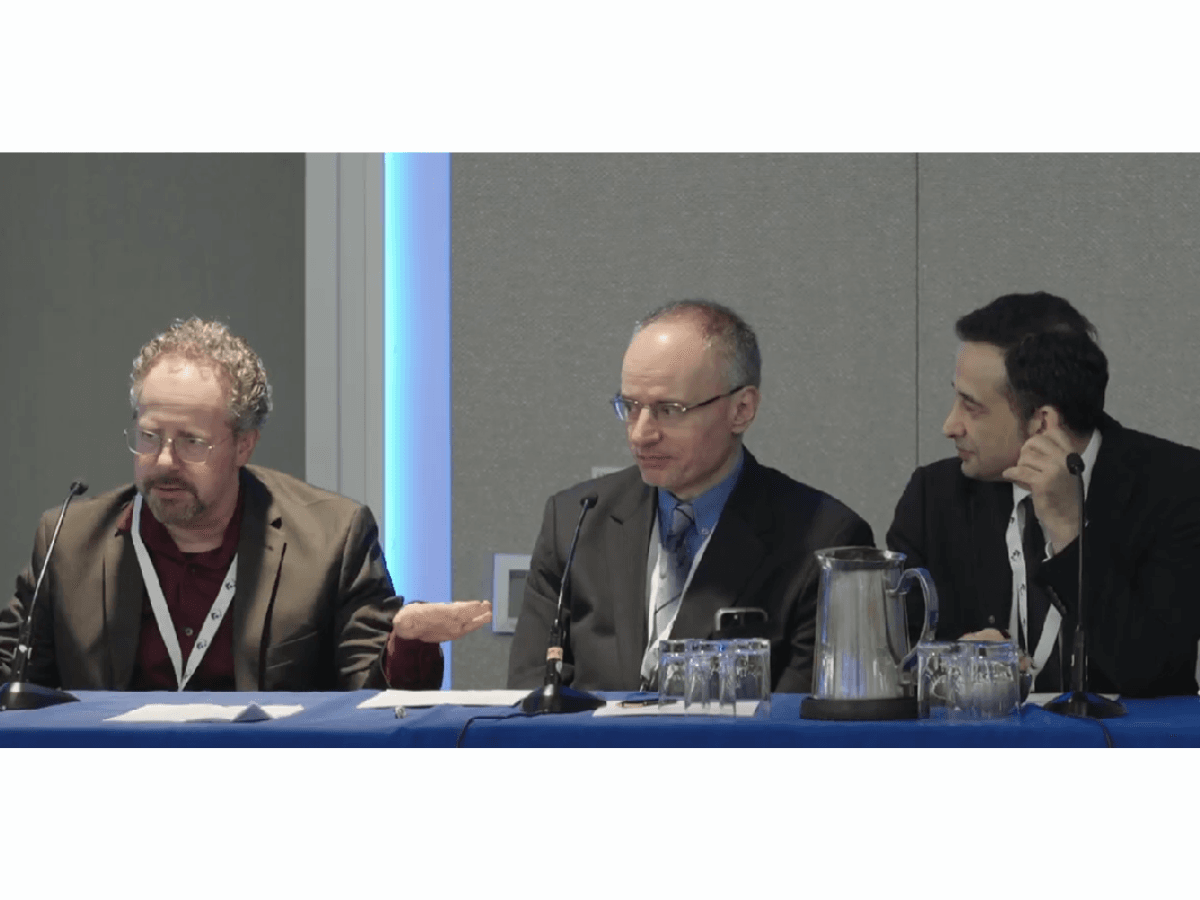

Pictured from left to right: Dr. Jason N Rosenbaum (Kaiser Permanente), Dr. Nicholas Mitsiades (University of California Davis), and Dr. Ibrahim Halil Sahin (University of Michigan Health)

This video shows a panel discussion at the Precision Oncology Summit, bringing together experts in medical oncology, molecular pathology, and translational research to address critical questions about when to use liquid biopsy, how to interpret results, and what the future holds for circulating tumor DNA testing in clinical practice. The session was chaired by Dr. Mamta Parikh (University of California Davis), featuring Dr. Jason N Rosenbaum (Kaiser Permanente), Dr. Nicholas Mitsiades (University of California Davis), and Dr. Ibrahim Halil Sahin (University of Michigan Health).

The transcript below has not been reviewed by the speakers and may contain errors.

Liquid Biopsy vs Tissue Biopsy: Clinical Decision-Making

The decision between liquid and tissue biopsy requires careful consideration of multiple factors. One critical yet underappreciated concern is the potential for detecting unrelated neoplastic processes. Liquid biopsy samples the entire circulatory system, which means it can pick up signals from any cancer present in the body, not just the one being monitored.

Hematological malignancies, in particular, can confound results. When mutations like KRAS or BRAF are detected in a patient with lung cancer, there's a risk these variants originate from circulating hematologic cells rather than the lung tumor itself. This misattribution could inappropriately exclude patients from effective targeted therapies.

However, this same characteristic—sampling the entire circulatory system—becomes an advantage when disease is known to be metastatic or suspected to be subclonal. Liquid biopsy captures the heterogeneity across multiple metastatic sites, providing a more comprehensive mutational profile than a single tissue biopsy.

Other practical considerations include tumor accessibility, patient tolerance for invasive procedures, and the risk-benefit calculus of tissue sampling in challenging anatomic locations.

The Challenge of Bone Biopsies in Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer presents a particular challenge since many patients develop bone-only metastases. While a bone biopsy can confirm metastatic disease, obtaining adequate material for next-generation sequencing remains problematic.

The primary issue stems from decalcification. Traditional histology lab methods for processing bone specimens use harsh decalcification agents that severely degrade DNA, rendering samples unsuitable for genomic analysis. Alternative decalcification methods that preserve nucleic acids exist, but they require extended processing times, a trade-off most clinicians find unacceptable in practice.

Even with optimal decalcification, bone metastases typically yield much less cellular material and DNA compared to soft tissue tumors. For these reasons, when soft tissue metastases are accessible, they're strongly preferred over bone sites for genomic profiling. If neither soft tissue metastases nor accessible primary tumor tissue is available, circulating tumor DNA becomes an essential alternative, though with the caveats about clonal hematopoiesis discussed throughout this article.

Complementary Roles: Why Both Tissue and Liquid Matter

Rather than viewing tissue and liquid biopsy as competing approaches, the field is moving toward recognizing their complementary value. Ideally, comprehensive genomic profiling should include both.

Tissue-based next-generation sequencing offers several distinct advantages. Panel testing from tissue typically covers more genes than liquid biopsy platforms. Crucially, tissue NGS can detect copy number alterations and other molecular abnormalities that circulating tumor DNA assays often miss. Tissue also provides the original clone's genomic landscape, establishing a baseline against which subsequent changes can be measured.

Circulating tumor DNA adds a different dimension. It can reveal additional clones that have emerged during treatment, particularly in highly heterogeneous metastatic disease. This is especially valuable when spatial heterogeneity means a single tissue biopsy may not capture the full spectrum of genomic diversity across multiple metastatic sites.

Clonal Hematopoiesis: A Critical Confounding Factor

Clonal hematopoiesis represents a major interpretive challenge for circulating tumor DNA analysis. This phenomenon—where blood cells acquire somatic mutations and expand clonally with age—can introduce variants into cell-free DNA that have nothing to do with cancer.

Some mutations clearly signal hematopoietic origin. When classic hematologic mutations like DNMT3A appear in circulating DNA, they're easily recognized as likely artifacts. The challenge arises with mutations that could plausibly come from either hematopoietic cells or solid tumors—TP53, KRAS, and NRAS being prime examples.

Is a detected KRAS mutation representing tumor evolution or clonal hematopoiesis? This ambiguity has significant clinical implications, potentially affecting treatment decisions. The solution requires matched white blood cell sequencing—essentially a buffy coat control that can distinguish germline variants and clonal hematopoiesis from true tumor-derived mutations.

Unfortunately, not all commercial vendors perform buffy coat sequencing unless tissue is also submitted for analysis. This creates a problematic situation: comprehensive interpretation of circulating tumor DNA may require upfront tissue sequencing, which provides germline and white blood cell baselines essential for proper variant classification.

Tumor-Informed Assays: Minimal Residual Disease Detection

Tumor-informed assays represent a specialized approach to liquid biopsy, particularly relevant in the minimal residual disease setting where curative-intent treatment is the goal.

In colorectal cancer, the limitations of TNM staging have become increasingly apparent. For stage III disease, only about 15 percent of patients actually benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, meaning the vast majority receive treatment they don't need, with all its associated toxicity and cost. Tumor-informed assays offer a path toward more personalized risk stratification.

These assays work by first sequencing the primary tumor to identify patient-specific mutations, then creating a customized panel to detect those exact variants in circulating DNA. This personalized approach theoretically reduces false positives from clonal hematopoiesis by focusing on a tumor-specific mutational signature.

The DYNAMIC study in stage II colon cancer has shown promise, particularly for stage IIA disease, where circulating tumor DNA negativity predicted only 5 percent recurrence risk—an acceptably low rate that might justify treatment de-escalation. However, for stages IIB and III, even circulating tumor DNA-negative patients showed 15 percent recurrence rates, which remains uncomfortably high.

The circulate-US trial is exploring sequential, repeated testing rather than single time points, which may provide more robust risk assessment. Importantly, these studies have identified a high-risk population—circulating tumor DNA-positive patients who show hazard ratios of 44 for recurrence—representing a clear unmet need for novel therapeutic approaches.

Tumor-Informed Assays in Advanced Disease: Limitations

While tumor-informed assays excel in the minimal residual disease context, their value in advanced metastatic cancer is less clear. When substantial tumor burden exists and circulating tumor DNA levels are high, standard broad-panel liquid biopsies may suffice, with commercial platforms increasingly adept at filtering out clonal hematopoiesis artifacts.

A critical limitation emerges when tumor-informed assays designed for minimal residual disease detection are applied to progressive metastatic disease. These assays track the mutational signature of the original tumor—often from a surgical specimen obtained months or years earlier. But metastatic cancer evolves. The dominant clone at progression may bear little resemblance to the original tumor.

This disconnect can create confusing clinical scenarios where circulating tumor DNA levels decrease even as the patient clearly progresses on imaging. The assay is detecting the original clone, which may indeed be shrinking, while a new resistant clone with different mutations drives disease progression. In bladder cancer, this phenomenon has been observed when tumor-informed assays based on cystectomy specimens are used to monitor metastatic disease.

Additionally, circulating tumor DNA levels fluctuate for reasons unrelated to treatment response. Systemic inflammation, infection, and other physiologic stressors alter the total cell-free DNA pool, which can change variant allele fractions even when tumor burden remains stable.

Clinical Utility in Advanced Colorectal Cancer

In metastatic colorectal cancer, liquid biopsy has found a clear clinical niche for identifying actionable alterations at diagnosis. The practice-changing BREAKWATER trial demonstrated that upfront genomic profiling enables precision medicine from the first line of therapy.

The reality of community oncology practice, however, often involves significant delays in tissue-based genomic testing. Turnaround times of two to three weeks are common, dependent on pathology support and workflow bottlenecks. This delays the initiation of optimal frontline therapy.

Liquid biopsy can return results in as little as a few days, allowing clinicians to start precision-targeted treatment immediately without waiting for tissue profiling. This speed advantage becomes particularly important as more targeted therapies move into frontline settings.

Interestingly, liquid biopsy has also revealed discordances with tissue testing that have prognostic and predictive value. In the FIRE-4 trial, patients enrolled based on tissue showing RAS wild-type colorectal cancer sometimes had RAS mutations detected in circulating tumor DNA. Ten percent had KRAS mutations, 5 percent had NRAS mutations, and outcomes for these liquid biopsy-positive patients were significantly worse, similar to those with tissue-confirmed RAS mutations.

Prospective Validation: Bladder Cancer MRD Studies

Bladder cancer has recently provided some of the strongest prospective evidence supporting circulating tumor DNA-guided treatment decisions. The IMvigor-010 study initially tested atezolizumab versus observation after radical cystectomy in high-risk bladder cancer. The primary endpoint was negative, showing no overall survival benefit.

However, exploratory analysis of tumor-informed circulating tumor DNA suggested that the subset of patients who were positive appeared to benefit from atezolizumab. Rather than relying solely on this retrospective signal, investigators conducted IMvigor-011, a confirmatory prospective randomized trial.

IMvigor-011 specifically enrolled circulating tumor DNA-positive patients and randomized them to atezolizumab versus observation. The study demonstrated a significant progression-free survival benefit with immunotherapy, the first prospectively validated evidence that circulating tumor DNA status can identify patients who benefit from adjuvant treatment.

The MODERN study is taking this concept further, randomizing patients based on circulating tumor DNA status to treatment versus no treatment. These bladder cancer studies represent a critical milestone in establishing minimal residual disease testing as a validated clinical tool rather than an investigational biomarker.

Challenges and Practical Considerations

Despite growing enthusiasm for tumor-informed assays, practical challenges remain. Unlike diagnostic genomic testing, which analyzes existing tissue samples with relatively quick turnaround, tumor-informed assays require an upfront sequencing step to create the personalized panel. This initial process takes considerable time, precisely when treatment decisions need to be made.

The circulate-US trial has encountered this issue in practice. By the time the tumor has been sequenced and the custom panel created, critical treatment windows may have passed. Once the assay is established, subsequent monitoring is rapid, but that first result comes at a crucial juncture.

Another reality is that tumor-informed assays require having adequate tumor tissue in the first place. For patients with bone-predominant disease, difficult-to-access primary tumors, or prior biopsies with insufficient material, tumor-informed approaches simply aren't feasible. This brings the discussion full circle to the tissue versus liquid biopsy considerations outlined earlier.

Longitudinal Monitoring: Promise and Uncertainty

Serial circulating tumor DNA testing over time offers potential advantages similar to what oncologists have long practiced with other circulating biomarkers. PSA monitoring in prostate cancer, for instance, has been standard for decades, demonstrating the value of longitudinal liquid biomarker assessment.

The predictive value of longitudinal circulating tumor DNA is clearest when new actionable mutations emerge. Detecting an ESR1 mutation in breast cancer, for example, signals resistance to aromatase inhibitors and potential eligibility for newer targeted therapies or clinical trials. Identifying such mutations before radiographic progression allows proactive treatment planning, avoiding the delay of waiting for scans, sending samples, receiving results, and then enrolling in studies—a process that can consume three to four weeks.

The more contentious question involves what to do when variant allele fractions increase, but no new actionable targets appear, and imaging remains stable. Some retrospective data suggest circulating tumor DNA elevation precedes radiographic progression by approximately 90 days. However, there's no consensus on what constitutes a meaningful increase, and prospective trials testing early intervention based solely on rising circulating tumor DNA levels are lacking.

Current practice—at least among cautious clinicians—involves using rising allele fractions as a trigger for more intensive monitoring with conventional methods: earlier imaging, additional scans, more frequent clinic visits. The goal is to detect progression through validated endpoints rather than changing treatment based on circulating tumor DNA alone.

This conservative approach reflects both the lack of prospective evidence supporting circulating tumor DNA-directed treatment switches and the significant limitations of variant allele fraction as a quantitative metric.

Understanding Variant Allele Fraction: Technical Limitations

Variant allele fraction—the proportion of mutant DNA relative to total cell-free DNA—is far less reliable than most clinicians appreciate. Unlike validated quantitative laboratory tests such as cholesterol or electrolytes, where the degree of measurement precision is well-characterized, variant allele fractions from next-generation sequencing carry substantial uncertainty.

The variability stems from multiple sources. Total cell-free DNA levels fluctuate based on non-malignant factors: inflammation, infection, tissue injury, and other physiologic stresses all contribute DNA to the circulation. Since variant allele fraction is a ratio of tumor DNA to total cell-free DNA, anything that changes the denominator alters the fraction even if absolute tumor DNA levels remain constant.

In tissue biopsies, variant allele fraction varies primarily because of sample heterogeneity—the small piece of tissue captured may have more or fewer malignant cells than another area. It reflects sampling variation, not necessarily disease biology.

Given these limitations, single variant allele fraction values should never drive clinical decisions in isolation. Trends across multiple time points become more interpretable. Concordant changes across multiple different mutations within the same sample also provide greater confidence. But relying on one variant allele fraction number, or a single change from the previous value, is methodologically unsound.

The PSA Analogy: Learning from Established Biomarkers

Prostate cancer's experience with PSA offers instructive parallels for how circulating tumor DNA might eventually be integrated into practice. PSA has served as a liquid biomarker for decades, with extensive data on doubling times, velocity, and their correlation with clinical outcomes.

Yet despite this wealth of experience, no prostate cancer therapy has ever received FDA approval based solely on PSA benefit without demonstrating clinical endpoints like overall survival or progression-free survival. PSA guides monitoring and informs decision-making, but doesn't replace validated outcome measures.

The same principle should apply to circulating tumor DNA. It serves as a useful tool for surveillance, for identifying emerging resistance mechanisms, and for risk stratification. But changing treatment, enrolling patients in clinical trials, or making other major decisions should still require validation through conventional endpoints.

Interestingly, some early data in colorectal cancer suggest circulating tumor DNA clearance may serve as a surrogate for outcomes, though this hasn't been rigorously validated, and the NCI doesn't yet consider it an acceptable surrogate endpoint. Cases where patients clear circulating tumor DNA on adjuvant treatment yet still recur highlight the potential for lead-time bias and the need for longer follow-up.

Patient Anxiety and Clinical Communication

An underappreciated challenge with circulating tumor DNA testing is the anxiety it can generate for both patients and clinicians when results are positive, but no clear intervention exists. This mirrors the experience with biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer—patients with detectable but low PSA after definitive treatment face uncertainty about when and whether to initiate systemic therapy.

With PSA, decades of data have established frameworks for risk stratification based on doubling time and absolute values. Fast doubling times signal aggressive disease requiring intervention; slow rises permit observation. Circulating tumor DNA testing currently lacks this granular decision-making infrastructure.

Identifying high-risk circulating tumor DNA-positive patients who desperately need better treatments represents a clear unmet need. But it also creates difficult conversations with patients who test positive, know they're at high risk, yet have no proven therapy beyond standard approaches. Balancing hope with realism, encouraging clinical trial participation without overpromising, and managing expectations all become critical communication skills.

Navigating the Commercial Landscape of Liquid Biopsy

The proliferation of commercial liquid biopsy platforms presents practical challenges for community oncologists. Multiple companies offer various tests with different intended purposes: comprehensive genomic profiling, minimal residual disease detection, tumor-informed assays, and mutation-specific panels.

Even within a single company's portfolio, there may be several different products designed for distinct clinical scenarios. Navigating this landscape—understanding which test is appropriate for which clinical question, what each platform's limitations are, and how to interpret results—requires ongoing education and experience.

For practicing oncologists, staying current with the evolving evidence base, understanding the technical capabilities and limitations of different platforms, and making informed decisions about when liquid biopsy adds value versus when tissue remains essential, all represent significant challenges. As the field matures, clearer guidelines and comparative effectiveness data will be essential.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

Several critical questions remain unanswered and represent active areas of investigation. Can circulating tumor DNA-directed early intervention improve outcomes, or does treating based on molecular progression without radiographic confirmation simply expose patients to additional toxicity without benefit? What magnitude and pattern of variant allele fraction change constitutes clinically meaningful progression? Can machine learning approaches integrate multiple biomarkers to improve risk prediction beyond what single measurements provide?

In the minimal residual disease space, optimal testing frequency, the role of sequential versus single time point assessment, and strategies for circulating tumor DNA-positive high-risk patients all need further study. The development of therapies specifically for this high-risk population represents a major unmet need.

Technical advances may address current limitations. Better methods for detecting copy number alterations from circulating DNA, improved filtering of clonal hematopoiesis, faster turnaround for tumor-informed assays, and integration of circulating tumor DNA with other liquid biomarkers like circulating tumor cells or tumor-educated platelets could all enhance clinical utility.

Conclusion

Liquid biopsy has moved from a research tool to a clinical reality, with clear applications in identifying actionable mutations, monitoring treatment response, and detecting minimal residual disease. However, appropriate use requires understanding both the technology's capabilities and its significant limitations.

The ideal approach often involves complementary use of tissue and liquid biopsy rather than choosing one over the other. Tissue provides comprehensive genomic profiling, copy number information, and a baseline for comparison. Circulating tumor DNA captures spatial heterogeneity, enables serial monitoring, and offers rapid results when tissue is inaccessible.

Critical interpretive challenges—clonal hematopoiesis, variant allele fraction variability, tumor evolution beyond the original clone—require awareness and clinical judgment. The field needs rigorous prospective validation before circulating tumor DNA results alone should guide treatment switching.

As the evidence base matures, particularly with studies like IMvigor-011 demonstrating prospectively validated utility, liquid biopsy will likely become increasingly integrated into standard care pathways. But that integration must be evidence-based, technically sound, and always centered on improving patient outcomes rather than simply generating data.

The most successful future for liquid biopsy lies not in replacing traditional approaches but in thoughtfully complementing them, guided by growing evidence about when, how, and for whom these powerful tools provide the greatest clinical value.