The Cancer News

AN AUTHORITATIVE RESOURCE FOR EVERYTHING ABOUT CANCER

New Study Offers Hope for Better Treatment Strategies: Understanding Blast Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) remains one of the most challenging forms of leukemia to treat, with limited evidence guiding therapy and historically poor outcomes. In this article, Dr. Akriti Jain, a leukemia specialist at Cleveland Clinic, explains the biology of blast phase CML and shares key insights from a large multicenter U.S. study presented at the 2025 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. The findings shed light on real-world treatment strategies, the role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and transplantation, and what these results mean for patients worldwide—offering renewed hope for improving outcomes in this aggressive disease.

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic phase has transformed from a life-threatening diagnosis to a manageable condition for many patients, thanks to targeted therapies called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). However, when CML progresses to blast phase, a more aggressive form of the disease, treatment options remain limited, and outcomes are often poor.

As a leukemia specialist atthe Cleveland Clinic, I am working to change that. In this article, I will be providing insights into the disease as well as what we have learned from the recent retrospective study that was presented at the 2025 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH).

How Myeloid Disorders Develop

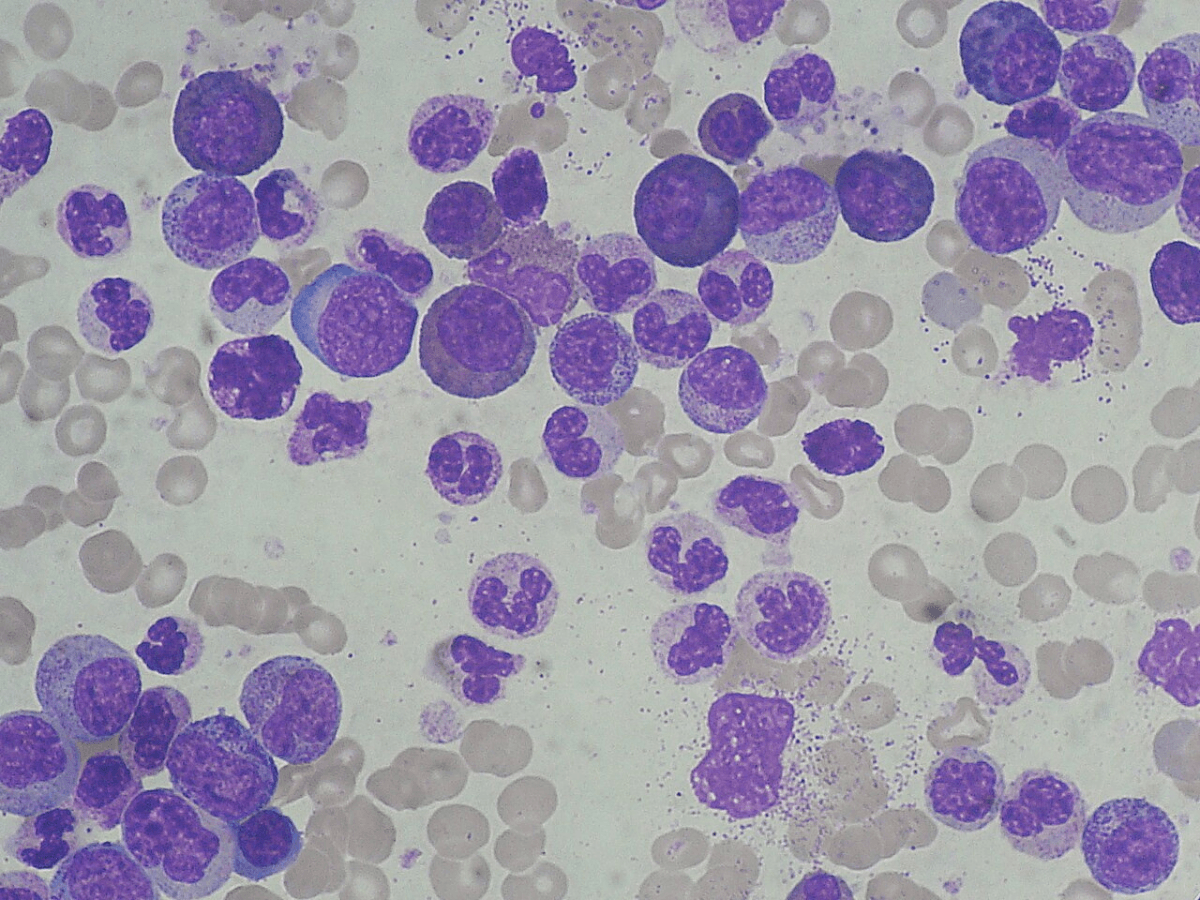

To understand blast phase CML, it helps to know how the disease begins. The bone marrow functions as a factory for blood cells, producing immature cells called blasts or stem cells that divide multiple times daily. These cells specialize into three essential types: white blood cells that fight infection, red blood cells that carry oxygen, and platelets that control bleeding.

This complex cellular division process is prone to errors. While DNA repair mechanisms typically correct these mistakes, certain factors can overwhelm these protective systems. Aging, previous chemotherapy or radiation, exposure to chemicals like benzene, chronic inflammation, and possibly autoimmune diseases can all increase the likelihood of errors accumulating in bone marrow cells.

These errors manifest as chromosomal abnormalities or DNA mutations. When a blast cell acquires certain mutations, it stops performing its normal function and instead produces more defective copies of itself. The specific mutation determines which type of myeloid disorder develops. For instance, the BCR-ABL fusion gene (Philadelphia chromosome) leads to CML, while JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutations result in myeloproliferative neoplasms like myelofibrosis.

The Evolution of CML Treatment

The landscape of CML treatment has changed dramatically over the past few decades. In the 1980s and 1990s, the only path to prolonged survival involved chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplantation. The approval of imatinib in 2001 revolutionized cancer care; it was featured on the cover of Time magazine: as they mentioned, “There is new ammunition in the war against CANCER. These are the bullets.”

Imatinib introduced the concept of targeted therapy, specifically blocking the abnormal protein produced by the BCR-ABL gene. Since then, additional Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) have been developed, including second-generation options (dasatinib, bosutinib, and nilotinib), third-generation ponatinib, and the novel STAMP inhibitor asciminib. These medications allow many chronic phase CML patients to achieve treatment-free remission, potentially living without active therapy while maintaining disease control.

Current Challenges for Blast Phase CML Management

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain. Many patients with chronic phase CML experience intolerance or resistance to TKIs, affecting their quality of life while taking these medications for years or even decades. More critically, blast phase CML—when blast cells exceed 30% in the bone marrow—represents a major unmet medical need.

Blast phase CML behaves like acute leukemia rather than chronic leukemia. Depending on the type of blasts present, it can resemble acute myeloid leukemia (myeloid blasts) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (lymphoid blasts). Yet patients with blast phase CML are typically excluded from clinical trials for both acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Treatment guidelines simply suggest following protocols for these acute leukemias without providing CML-specific evidence or consensus.

A Multicenter Study Analysis to Fill the Knowledge Gap

My recent research addresses this critical gap in knowledge. The impetus came from a European study published in March 2024 that examined 240 blast phase CML patients through the European Leukemia Network's registry. That study revealed highly heterogeneous treatment approaches—patients received various chemotherapy regimens without clear patterns—and reported a median overall survival of only 23.8 months.

This prompted me and my mentors in the HJK Cure CML consortium to ask: What treatments are being used in the United States, and which approaches yield the best outcomes? Since blast phase CML is relatively uncommon, the research team combined data from multiple institutions to analyze 288 patients, examining which chemotherapy regimens were used, which TKIs were combined with chemotherapy, and what outcomes patients experienced.

The goal was to identify which treatment strategies lead to the best results, potentially establishing a standard of care for blast phase CML where none currently exists.

Key Findings and Clinical Implications

The study reaffirmed several important principles while offering new insights. Multivariable analysis revealed that outcomes were similar whether patients received a TKI alone, followed by transplant, or TKI plus chemotherapy, followed by transplant. The critical elements appear to be TKI therapy combined with transplantation to achieve the best overall survival, though questions remain about whether mild chemotherapy might be beneficial.

Interestingly, on univariate analysis, the generation of TKI used, first, second, or third, did not significantly impact overall survival, as long as patients received some form of TKI. While third-generation TKIs showed numerically better outcomes, the differences were not statistically significant in the final analysis.

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Treatment Access: Global Equity Challenges

This finding has profound implications beyond the United States. Many countries, particularly in the developing world, lack access to second and third-generation TKIs. Cost presents another significant barrier—generic imatinib is relatively affordable and widely available, while newer TKIs can be prohibitively expensive.

While most blast phase CML patients should ideally receive second or third-generation TKIs, the choice also depends on whether blast phase was diagnosed initially (de novo) or developed after chronic phase CML (which carries a poorer prognosis), as well as which TKI was used during chronic phase treatment.

Our research underscores the importance of patient advocacy, working with healthcare providers to obtain the most effective medications available, and understanding treatment options to make informed care decisions.

What Are The Next Steps in Understanding the Management and Outcomes of Blast Phase CML?

Our research team continues to strengthen its analysis by collecting additional data from participating institutions. Future work will examine the impact of mutations detected through next-generation sequencing and tyrosine kinase domain mutations on patient outcomes. Once published, this comprehensive analysis will provide clinicians with evidence-based guidance for treating blast phase CML.

While retrospective studies like this one typically do not immediately change clinical practice—that distinction belongs to randomized phase III trials—they provide crucial evidence that can inform treatment decisions and advocate for patients when definitive trials are not feasible for rare disease presentations.

For patients and caregivers facing a blast phase CML diagnosis, this research offers both practical guidance and hope. It demonstrates that the medical community is actively working to understand and improve outcomes for this challenging condition, and it provides evidence that effective treatment is possible when TKI therapy is combined with transplantation. Perhaps most importantly, it highlights the need for patients to work closely with their healthcare teams to access the best available therapies, regardless of geographic or economic barriers.

About the Author

Dr. Akriti Jain is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and Associate Staff at the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Leukemia and Myeloid Disorders Program at Cleveland Clinic. Born and raised in India, Dr. Jain completed medical school there before pursuing residency and fellowship at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida. Her passion for treating myeloid disorders was sparked by a close family member's diagnosis with chronic myeloid leukemia during her residency. Dr. Jain specializes in treating patients with leukemia and myeloid disorders, including myeloproliferative neoplasms such as myelofibrosis, essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and chronic myeloid leukemia. Her research focuses on improving outcomes for patients with CML, particularly those with advanced disease.